Cool. Elegant. Understated.

These words are as applicable to the work of Donald Allan Wexler as they are to the man himself. Wexler is that rare breed of architect — one who practices humility. His buildings, never overwhelming, are filled with sophistication, ingenuity, and a marvelous ability to put every square inch to use in a universally economic and thoughtful manner. However, Wexler does not design the kind of building meant to knock your socks off; hence they remain timeless in their simplicity, in their classic proportions and refinement.

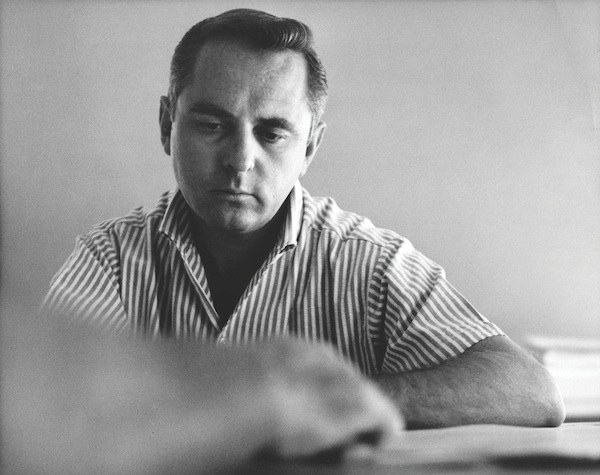

PHOTO COURTESY OF DONALD WEXLER FAMILY COLLECTION

Donald Wexler came to Palm Springs to work in the office of the great architect William Cody.

Wexler was lured to Los Angeles from Minnesota by a chance job offer from his architectural idol, Richard Neutra. Subsequently, he came to Palm Springs to work in the office of the great architect William Cody. It was at Cody’s practice that he met Richard Harrison, with whom he would form the partnership of Wexler and Harrison, responsible for a significant percentage of the finest midcentury modern architecture found in the desert.

Like many of our regional architects, Wexler was called upon to do a wide variety of building types — homes, offices, banks, and schools. Whatever building type was thrown his way, Wexler reacted with the intelligent response that he continually brought to bear on projects, regardless of the task at hand. To each of these structures, there is a simplicity that belies the complexity within.

PHOTO COURTESY OF GLEN WEXLER

The Palm Springs International Airport began life as Los Angeles’ “relief airport” for when the coast was socked in by clouds. It grew as more and more airlines discovered the city’s tourist appeal. Wexler’s philosophy about air travel forged the design. “Passengers have been forgotten in the air age,” he said, “so we designed this building for the passengers, not the planes. The buildings form an X; passengers can see everything from one corridor without the use of confusing signage.” A putting green that many considered one of its most distinctive characteristics was removed in a renovation.

With the Alexander Steel Houses of 1961–1962, Wexler and Harrison (with Bernard Perlin) created an ingenious methodology for home construction. Starting with a prefabricated core consisting of a kitchen, two bathrooms, and all of the mechanical systems of the house, and surrounding it with prefab wall modules, they built the houses in a mere four weeks, start to finish.

Although these houses are not huge by any means, at approximately 1,400 square feet each, there is never a feeling of claustrophobia in any of the spaces. In the wonderfully designed kitchens, for example, one can see above the cabinets, through a pass-through, and also underneath the cabinets. This gives these small kitchens a seamless flow into the adjacent rooms, with wall-to-wall glass connecting the small spaces into a significantly greater whole while fusing exterior spaces into the interiors.

Photography by Julius Shulman & Juergen Nogai/© Juergen Nogai

The Dinah Shore House by Wexler (1964) in Palm Springs. The property has been renovated with materials Wexler would have used during the original construction.

This innovative format can be seen in the numerous schools that Wexler designed, spaces intended to educate and inspire students to be aware of the singular context that is Palm Springs.

In the demolished Palm Springs Spa Bath House (the site of the original hot springs that gave Palm Springs its name), Wexler’s concept was again simple yet thoughtful. A cast concrete colonnade ran alongside a pool of water in such a manner that sunlight would bounce off of the reflecting pools onto the underside of the colonnade, creating a sinuous ripple of reflected water, a perfect homage to the natural springs that occur there.

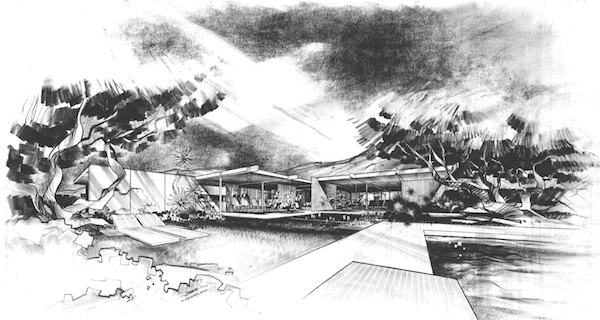

rendering courtesy of palm springs art museum

This illustration shows Wexler’s original draft design for the Dinah Shore House.

Wexler’s superb Dinah Shore House (1964) again shows his ingenuity. Rather than place the house squared to its site, Wexler rotated it so that the home sits on a diagonal axis, creating a break with the other houses on the street that run parallel to it. Much of Palm Springs’ architecture is “discreet to the street,” i.e., the street presence is understated so as not to conflict with the immediacy of the mountains. The Dinah Shore House is especially so, in that its façade is completely opaque, giving total privacy from the street. Inside, however, the house frames a marvelous, spacious backyard through expansive walls of glass.

Perhaps Wexler’s greatest achievement is the Palm Springs airport main terminal (completed in 1965). Clearly built during the Jet Age, the building subtly, and perhaps unconsciously, evokes the shape of a jet plane about to take off. Arriving at the Palm Springs International Airport is a celebratory experience, with the marvelous interplay between interior and exterior, and the wallop of the proscenium-like main lobby that frames, and defers to, the spectacular view of Mount San Jacinto. When you arrive at the Palm Springs airport, you know you have arrived at a special place in the world, a place that Donald Wexler was instrumental in bringing to life in his numerous, joyous works.

Residents and visitors alike are grateful to the modest Wexler, whose humility belies the true marvel of his creations.

This is the eighth of a nine-part series adapted from The Desert Modernists: The Architects Who Envisioned Midcentury Modern Palm Springs. The book, published by Modernism Week in partnership with Palm Springs Life, was released in February 2015 to coincide with the 10th anniversary of Modernism Week. This chapter’s author, Michael Stern, curated the exhibition Julius Shulman: Palm Springs; co-authored the Rizzoli publication Julius Shulman: Palm Springs; and directed the film Julius Shulman: Desert Modern, which aired on PBS. Stern leads architectural tours of Palm Springs for individuals and groups in conjunction with the Palm Springs Art Museum Architecture and Design Center, Edwards Harris Pavilion.