Marigold Linton suffered more than the usual mortifications while growing up on the Morongo Indian Reservation — where the Cabazon outlet stores are today. She was poor (no television or electricity). She was outcast (white kids shunned her because she was Indian, and Indians shunned her because she was part Japanese). And her kooky grandfather living out back in his homemade “Catclaw Siding” shack did not help her cause.

Though she had been warned to stay away from the old man because of his drinking, Linton remembers sneaking over to pick chokecherries and browse in the alcove where he taped up newspaper clips of his famous friends: Walt Whitman, Gertrude Stein, Isadora Duncan, John Barrymore, and others.

Linton’s grandfather — Sadakichi Hartmann — has been called the High Priest of American Art. The New York Sun dubbed him “King of the Bohemians.”

Kichi, as he was called, wrote the first history of American art, was the first to critique photography as an art form, and edited and published two of the first avant-garde magazines in America. He was the first to write haiku and tanka in English, influencing poets such as Ezra Pound. He engineered the first light show and the first perfume show years before the hippies were born. He also was a playwright, an actor, and a dancer, famous at Hollywood parties for his “hands dance.” In sum, Hartmann was a brilliant dervish who spun through the world setting off sparks in others.

Son of a German trader and a Japanese mother, Hartmann was born in Japan in 1867 and raised in Hamburg, Germany. He was kicked out of the house by his father at age 14, and sent to live with a relative in America — a bitter memory that may have spurred his rebelliousness. He wrote his first play, Christ, at age 23 and was promptly banned in Boston. He lived in Philadelphia for a time, where he fried eggs with Walt Whitman and translated correspondence for the beloved poet.

Moving to California in 1916, Hartmann appeared in Douglas Fairbank’s Thief of Baghdad. He published 12 plays and nine books, including My Crucifixion, an account of the brutal asthma that forced him to sleep upright and eventually drove him to seek relief in the San Gorgonio Pass.

Along the way, according to a 1944 obit in Time Magazine, he managed to marry three times and fathered 15 children, naming one set of offspring after jewels, another after flowers.

One of the flower children, Wistaria, married a member of the Morongo Indian tribe, Walter Linton. That connection, as well as Hartmann’s health problems, brought him to Beaumont in the early 1920s. He later moved onto his daughter’s property on the reservation, where he built his shack and made paintings of Mt. San Jacinto from his porch.

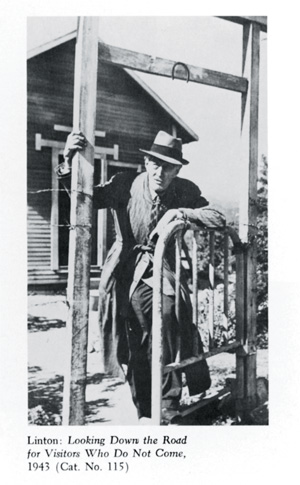

The bohemian tramped the streets of Banning and Beaumont with his gangly frame wrapped in a long overcoat. Locals were suspicious of this oddball with his intellectual bent and exotic face, once described by a writer as a “face of a thousand sad secrets” with “eyes of mystic agony.”

Beaumont resident Betty Meltzer says he was looked down upon for his Japanese ancestry (“That didn’t sit well with people when World War II came along”), as well as his increasingly heavy drinking. “He dropped into anonymity when he moved to this area,” she says.

In the larger world, he is hardly anonymous. A search of the Internet shows he has attained minor cult hero status. And at UC Riverside Special Collections, the staff gets more requests for their Hartmann collection than any other holdings.

The little girl who grew up poor and outcast in Morongo is today a cognitive psychologist, as well as director of American Indian Outreach for the University of Kansas. Her mother, Wistaria Linton, died on Feb. 5 at age 95, and Marigold is sorting through the boxes of writing her grandfather left behind when he died, a task she says will take her approximately 170 years: “Every time I open a box I say, ‘Oh Lord.’”

The last photograph of Sadakichi Hartmann, taken in 1943 on the Morongo Indian Reservation.

Wistaria Hartmann Linton