Albert Frey's arrival in our desert is one of the most pivotal and important moments in local history.

Fresh off the huge success of their futuristic, metal-clad Aluminate House of 1931, toured by more than 100,000 attendees in only one week during a New York exhibition, Swiss-born Albert Frey was asked by his partner, A. Lawrence Kocher, to design a combination apartment and office building for Kocher’s brother, who lived in a remote desert outpost called Palm Springs, California.

The Kocher–Samson Building (1934) still stands on Palm Canyon Drive. Its long-wished-for restoration will herald once more how serious Palm Springs really is about its world-recognized heritage. It is with that building that the legacy of Palm Springs international modernism was born.

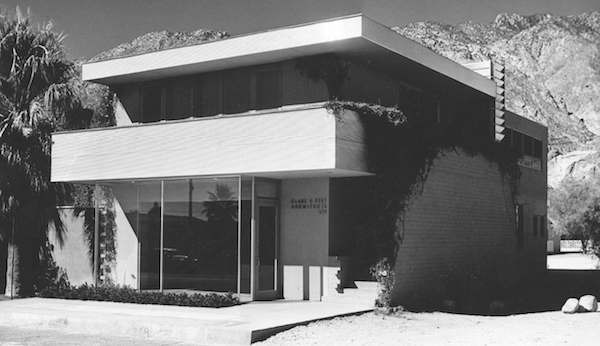

Clark & Frey Building, 879 N. Palm Canyon Drive.

How this well-known and highly experimental designer and architect (he would in fact not get his actual California architect’s license until 1943) came to our desert is one of the many fortuitous twists of fate that Palm Springs should be most thankful for. Of course, spring water, celebrities, resale shops, and cement ponds jockey for ranking on the list as well.

Frey fell in love with the desert and settled here permanently in 1939 after a few back-and-forths from the East Coast. His work is synonymous with a Palm Springs modern style, but it is much more than that.

It is an international interpretation of not only a vernacular but also a contextual expression of a category shaped and defined by location. Frey’s Desert Modern idiom addresses the necessities of the extreme conditions within a sophisticated, Swiss-filtered, modern language of his own design.

In his most important commissions — the aforementioned Kocher–Samson Building, Palm Springs City Hall (1952), the Tramway Valley Station (1963), Frey House II (1964), and the Tramway Gas Station (1965) — you are witnessing the combination of geographically sensitive materials manipulated and assembled with the precision and modesty of a smart Swiss watchmaker.

When discussing International Style and modern architecture, all roads lead to or from Le Corbusier. The esteemed architect David Chipperfield echoes almost all of his peers when he proclaims that Le Corbusier was “without doubt the greatest architect of the 20th century.” Frey was employed by the master in Paris in 1928 as one of only two full-time employees, and he worked on such seminal Corbu projects as the Villa Church (1927), the Villa Savoye (1929), and Maison Loucheur (1929).

Frey and Le Corbusier remained friends for many years; letters between the two reveal a real camaraderie and show that Frey had found his true home in Palm Springs. “It is a most interesting experience to live in a wild, savage, natural setting,” Frey wrote, “but without losing contact with civilization due to the intellectual milieu of Palm Springs and the presence of visitors from all parts of the world. Moreover, the sun, the pure air, and the simple forms of the desert create perfect conditions for architecture.”

The Kocher-Samson Building.

“Simple” and “pure” best describe Frey’s work. He was a master of understatement, eliminating the insignificant, and in doing so, foreseeing the minimalist movement by decades. In fact, one of the biggest dangers a Frey building faces is people’s urge to slap things on it or encrust it over the years.

For example, see the Southwestern-style paint job on the Tramway Valley Station, or even the well-meaning but damaging attachment of a large bronze recognition plaque right on the front of the sublime Fire Station No. 1; or the copper band and giant rooftop compressor headaching the City Hall chambers. These buildings are like minimalist paintings or Donald Judd sculptures — why mess with them? Less is more. Original is better. The purity must be upheld.

We often think of Frey’s architecture as not only striking and angular but also as something that comes only in shades of gray. Yet Frey was a sensitive master of color. He understood the desert and the colors that complemented it like few others.

The soft salmon of his sandblasted building blocks; the bright blue he used for the corrugated anodized aluminum ceiling panels; the rusting Corten steel so reminiscent of the dark browns and bronzes of the sunbaked local rocks; the encelia yellow of his drapery; the perfect, muted sage greens of his wonderful asbestos siding — his best work is undemonstrative in its sublime hues but potent in its sensitivity to site and purpose.

Frey House I, at 1150 Paseo El Mirador in Palm Springs. It was later demolished.

Long before it was fashionable, Frey employed industrial materials in residential and commercial settings. He reached for longevity with his vocabulary of architectural materials.

Frey aspired to maintenance-free buildings that didn’t need to be painted inside or out. (He used concrete block, fiberglass, asbestos siding, and aluminum windows.) He eschewed gypsum board and often clad his interiors in ceruse wood paneling. His buildings resisted earthquakes, rotting, and warping. His goal was timelessness both in materials and style, and he created a simple look that resists the winds of fickle fashion and is constructed in almost indestructible materials.

Frey wanted longevity not only in architecture but also in his own life. He followed a strict diet and practiced yoga religiously (although his sweet tooth is rather legendary). Eventually, his home up on Palisades Drive went dark when Frey died at age 95 in 1998, but it is still a beacon of Desert Modern style: He gifted the home to the Palm Springs Art Museum, and it has become the most popular attraction of every Modernism Week.

Frey is buried in historic Welwood Murray Cemetery at the base of the hill he loved so dearly and called home for 64 years. A rugged footpath leads directly down from his famed home to his final resting spot.

• • • •

This is the second of a nine-part series adapted from The Desert Modernists: The Architects Who Envisioned Midcentury Modern Palm Springs. The book, published by Modernism Week in partnership with Palm Springs Life, will be released in February 2015 to correspond with the 10th anniversary of the 10-day event, Feb. 12-22, 2015. For more information, visit www.modernismweek.com. The author of this chapter, Brad Dunning, is a designer known for working on architecturally significant properties, restorations, and contemporary design. In addition to his own designs, he has worked on homes by such architects as Richard Neutra, Wallace Neff, A. Quincy Jones, Albert Frey, John Lautner, and others. He has also written about architecture and design for The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Interview, and Vogue, and was a contributing editor on architecture and design for GQ. He also gives talks and lectures about architecture and design.