There is an argument to be made that Novak Djokovic is the most under-appreciated, under-idolized superstar athlete in the world.

That’s not likely to change when he arrives in Indian Wells this month for Larry Ellison’s desert oasis of opulence, also known as the BNP Paribas Open, March 7–20. It is to tennis what Opus One is to wine. Djokovic is playing for his third consecutive and his fifth overall title.

Djokovic arrives as the top-seeded male player, especially after his straight sets win this year in the Australian Open over Andy Murray. Djokovic’s performance in 2015 was so near perfect that even Bo Derek would hold up a 10.

Coached by six-time Grand Slam title winner Boris Becker, Novak Djokovic is known as one of the fittest and best prepared players in professional tennis.

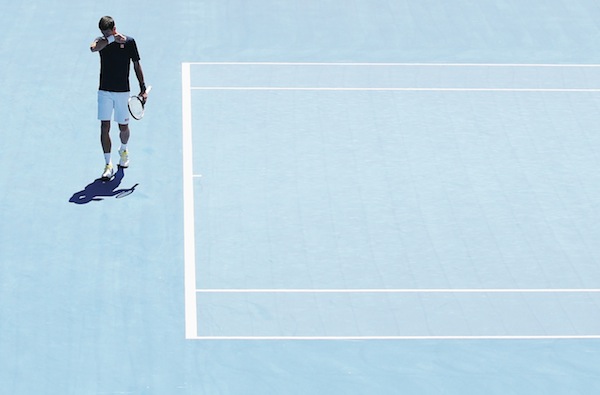

Photo by Billie Weiss/BNP Paribas Open

Last year, he won three of the four major tournaments, the Australian, Wimbledon, and the U.S. Open. The only one he lost was the French, and that was in the final. The tennis world buzzed all year about Serena Williams’ quest for a calendar-year Grand Slam, but then she lost in the U.S. Open semifinals in New York City in September. Djokovic’s season turned out significantly better than the American’s: He went one round farther in his overall Grand Slam season.

When Palm Springs Life spoke to Djokovic recently, it was clear that an unusual sense of perspective is responsible for how he handles public perception that he’s second fiddle. Others of his athletic stature often seem entitled to reverence; Djokovic never seems to forget that he is lucky, and obliged to acknowledge it. “[Going] through the certain unusual experiences in my life has definitely made me appreciate and value the things … I received, that I lived through,” he says.

He speaks as a recently married father — his son is 1 ½. But now, at 28, his stellar performances often get lost. You wonder why.

When he first gained prominence, in 2007 with a runner-up finish at Indian Wells, fans struggled to pronounce a name that started with two consonants. Journalists, at least the English-speaking ones, struggled to make fingers type D and J consecutively.

“[My] experiences through the war, and being left with nothing and not knowing, really, what tomorrow will bring, kind of shaped my willingness [to give back.]”

Photo by Billie Weiss/BNP Paribas Open

Then there were Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal. Tennis was not looking for new royalty, didn’t need any. Federer and Nadal were taking turns on the throne, and you could pronounce and spell their names. The more the merrier works in most sports, but tennis had plenty going for it with the frequent Federer-Nadal matchups that were so competitive and dramatic that they defied description.

Djokovic persevered. What else could he do? You can’t make Miss America ugly and you can’t make Federer and Nadal unpopular.

He followed up his loss in the 2007 Indian Wells final to Nadal with a prestigious title two weeks later in Miami, beating Nadal in the quarterfinals. Then he marched all the way to the final in the U.S. Open, amid the noise and nuttiness that is the trademark of that New York City event. But even before his loss in that final to Federer, he got everybody’s attention without even swinging a racket.

After an early round victory, he was doing an on-court interview for the fans in Arthur Ashe Stadium and the usual huge TV audience. The interviewer, abandoning the usual tripe of “how did you feel?” and “were you happy with your serve?,” said he had heard that Djokovic was very good at imitations of other players and was known around the locker room for such goofiness. Would he do some for the fans?

Djokovic’s wide-eyed look indicated that this was no preplanned setup. Pushed a bit, he complied.

Novak Djokovic turned pro at age 16.

Photo by Billie Weiss/BNP Paribas Open

First came Nadal, sprinting back and forth, twitching and fidgeting, then tugging on his shorts as he got ready to serve. The crowd howled. Next was his Maria Sharapova, her back very straight, her countenance deadly serious, taking tiny steps away from the service line to have her little chat with herself and her racket before returning to the line and brushing away a strand of hair before going into her service motion.

The stadium’s 20,000 fans roared with delight. A star was born. Most people didn’t even know if he could really play, but now they knew tennis had an up-and-coming player who might make it on Saturday Night Live.

To journalists who had struggled to type his name or remember which Eastern European country he came from, the appropriate nickname was too easy: the Djoker.

A Childhood Forged by War

Djokovic’s formative years were anything but funny. As a child in war-torn Yugoslavia, his family had waited in bread lines and endured nightly bombings for months in the spring of 1999. The late Jelena Genčić, the woman who discovered his tennis skill when he was 5, telling his parents he was a “gift” and a “prodigy,” used tennis courts for her lessons in areas of Belgrade bombed the night before, assuming that NATO forces would not return to the same places.

Djokovic’s introduction to the sport was happenstance. When he was 2, his family moved from Belgrade and ran a cafe called the Red Bull Pizzeria. It was in the mountains in the city of Kopaonik, a prime ski area. Djokovic’s father, Srdjan, and his uncle and aunt were all pro skiers. The family held ski lessons during the day and waited on tables at night. When a Yugoslav-owned development company named Genex built housing near the Red Bull, they put in some tennis courts. Four-year-old Novak found a racket and the courts, and Genčić soon found him.

In 1999, with the bombings at their worst in more than 11 weeks, the Djokovic family scraped together funds to send 12-year-old Novak to Munich and former world No. 6 Niki Pilić’s tennis academy. Four years later, after winning several major junior tournaments, Djokovic turned pro.

Novak Djokovic first gained prominence in 2007 with a runner-up finish at Indian Wells.

Photo by Billie Weiss/BNP Paribas Open

He was two months shy of his 20th birthday when he lost in the Indian Wells final in 2007. After Miami, he won the Rogers Cup in Montreal, an event, like Indian Wells and Miami, with prize money and stature just a notch below the four majors, taking out, in order, No. 3 Andy Roddick, No. 2 Nadal, and No. 1 Federer. A sweep of the world’s top three players in one event hadn’t been done since 1994.

Then, in the U.S. Open, he imitated and played his way into the hearts of tennis fans by making it all the way to the final. Even better, for most of those fans, he lost to their beloved Federer. Djokovic’s 2007 season was the springboard to longtime success, or so everybody thought.

He began 2008 by winning the Australian Open, his first major title. He also won his first Indian Wells title, beating Nadal in the semifinals and Mardy Fish in the final. Tennis writers started calling the elite group at the top of men’s tennis the Big Four — Federer , Nadal, Andy Murray, and the kid from Serbia with the flexibility of a rubber band and the will to hit one more ground stroke than the guy on the other side of the net. It had been a long ride from the bread lines of Belgrade to this lofty perch. He had made it.

In 2009, he was No. 3 in the world. Same in 2010. It wasn’t enough for the competitive Djokovic, especially when every question he was asked in every news conference was about looking up, about being happy with where he was. Djokovic might have seethed with resentment, but he was always a gentleman.

“Roger is a legend,” Djokovic would say, in one form or another, time after time. “It is just an honor to be considered a player on his level.”

Despite leading Serbia to its first-ever Davis Cup title in 2010, despite his No.3 ranking, despite winning on the tour, he had not won another major title. They are what every tennis pro lives for and dreams about.

By 2011, at 24, Djokovic had a new, gluten-free diet and a renewed commitment to fitness. He won the Australian Open and two more majors, Wimbledon and the U.S. Open. The French Open remained his Achilles Heel. Still does. At the time, nobody but Nadal was winning the French. Still, by the Fourth of July, Djokovic set off a few fireworks; on that day, he became No. 1 in the world for the first time.

He beat Nadal in the U.S. Open final, after beating Federer in the semis. He had four major titles enroute to his current 11, and the world took note. Five years later, he is a man of the world who speaks five languages — French, English, German, Italian, and Serbian -— who hungers to win a calendar-year Grand Slam. And he’s not content with 11 Grand Slam titles because they leave him seven behind the man with the most. Federer.

Despite defeating the Swiss maestro in the last two Wimbledon finals and the last U.S. Open final, the crowd still roots for Federer. The crowd isn’t anti-Djokovic; just pro-Federer. Federer’s appeal is international. Djokovic is smart enough to know that Federer’s game, longevity, and regal personality command respect, and if he resents it, the public will never know.

But they are learning something about the man as well as the athlete.

The World Beyond the Locker Room

The day after he lost to Murray in the 2012 U.S. Open final, Djokovic held a dinner in New York City for his eponymous foundation for underprivileged children. He raised $1.4 million that night. In 2013, he lost again in the final, but his dinner in New York City raised $2.5 million.

He has been honored for his charitable work by UNICEF, has spoken at the United Nations in support of the International Day of Sport, has received the Arthur Ashe Humanitarian Award, and the Aces for Charity Award from the ATP Tour.

As he told Palm Springs Life, “Giving back is not just something that is important to me or any other successful personality,” he said. “It’s a responsibility you need to carry with you, being so successful in your life and giving back to the people who are less fortunate.

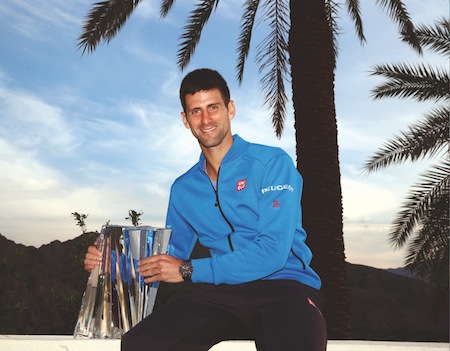

Last year, Djokovic won three of the four major tournaments, the Australian, Wimbledon, and the U.S. Open.

Photo by Michael Dodge, Getty Images

“The mission of our foundation … [is] education for children … [E]ducation is a pillar and a base for success in your life … something that nobody can take away from you. We’ve selected that because we want to invest in the future.”

The norm for professional athletes is to focus on little outside of their opponents and their wallets. Not Djokovic.

Last summer, as the Special Olympics World Games in Los Angeles approached, word reached Djokovic that funds were running short in Serbia and that some of its disabled athletes might have to be left at home. Djokovic wrote a check, reportedly for about $30,000, and the Serbian National Special Olympics team arrived intact. More significant than the check was the lack of self-promotion. There were no news releases or publicity. Djokovic is not among the sports stars whose enablers call 25 reporters and photographers before they visit a children’s hospital.

“You want to invest in the future or invest in kids,” Djokovic told Palm Springs Life. “[My} experiences through the war, and being left with nothing and not knowing, really, what tomorrow will bring, kind of shaped my willingness [to give back.]”

“When you see a child smiling,” he said, “it’s like you see the sun ….”

After an early round match in the 2014 U.S. Open, he was about to end his news conference when he asked the moderator for an additional minute or two. In the first row of the room was a 9-year-old girl named Zia Uehling sitting on her father’s lap. Gordon Uehling was a former tour player.

Djokovic said that they were friends, that Zia was a music prodigy. He said he wanted Zia to meet the press and find out what it’s like to be in the public eye. He hadn’t told Zia or her father what he was going to do. He invited them to the news conference and told them to sit in the front row.

“Ask her a question,” Djokovic said, urging the press corps. “Please.”

Reporters did, one asking if she wrote her own songs. When she said yes, he asked her to sing it.

Standing next to Djokovic, Zia sang to the room with no hesitation or stage fright. Several dozen grizzled and harassed reporters on deadline were serenaded by Zia Uehling’s “African Sun.” Nobody left the room.

Djovokic beamed as if she were his own child. “Hey guys,” he said, “keep talking to her. I’ll get out of the way,” and headed for the door.

The Djokovic Files

In 2015, besides Novak Djokovic’s three major victories, and the close call at the French Open, he:

• won 86 matches and lost six, three of them to Federer (Only Federer, 92-5 in 2006, Jimmy Connors, 93-4 in 1974, and John McEnroe, 82-3 in 1984, have done better)

• won a season-ending title in the tour championships, his fourth in a row and his fifth overall

• finished the year ranked No. 1, and when the BNP Paribas tournament starts, will have been so ranked for 189 weeks

• won $21 million in prize money

• dominated the men’s tour with 11 titles, and reached the final in 15 of his 16 events, including 15 in a row