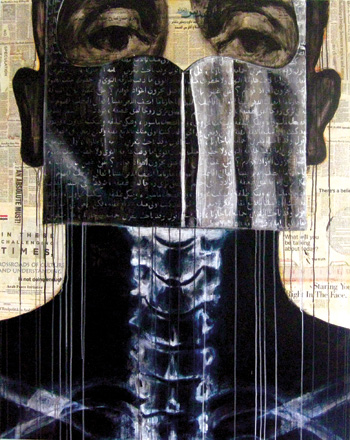

A figure hangs from a noose in a field of black paint — an arresting image with line after seemingly endless line of curious, white-painted Arabic calligraphy. On another canvas, a body shrouded in white and set into a dark space bordered by a field of calligraphy lies anonymously in a coffin, never to receive proper burial. And a black-and-white painting of a handsome young man, presumably the Iraq-born artist himself, appears either intent or afraid to speak of his personal story as fiery orange and red lines of calligraphy stretch from one side of the canvas to the other, a cacophony of words covering his mouth.

Paintings by Palm Springs-based artist Ayad Alkadhi, whose earlier thick, carved calligraphic paintings celebrated Baghdad’s rich cultural tradition, have flattened over the years and now respond to the U.S.-led war in Iraq — the tens of thousands of unreported Iraqi casualties, the looted and destroyed institutions, and the prisoners of Abu Ghraib.

The artist’s role in times of war, historian Howard Zinn wrote, “is to transcend conventional wisdom, to transcend the word of the establishment, to transcend the orthodoxy, to go beyond and escape what is handed down by the government or what is said in the media.”

The artist’s role in times of war, historian Howard Zinn wrote, “is to transcend conventional wisdom, to transcend the word of the establishment, to transcend the orthodoxy, to go beyond and escape what is handed down by the government or what is said in the media.”

Alkadhi offers incisive commentary on the Iraqi death toll, infusing and sometimes juxtaposing iconography of Near East and Western politics and religion. He belongs to a generation of artists seeking to retain their ethnic identity while assimilating into Western culture. His use of Arabic newspaper on mixed-media canvases, as well as in calligraphy, connects traditional Arabic to powerful, cutting-edge expressions of the artist’s perceived existence as a U.S. resident constantly explaining his thoughts on the war, Saddam Hussein, and the U.S. occupation of Iraq. “After Abu Ghraib, something switched,” Alkadhi says. “Part of survival is to detach. I tried to justify the Americans’ actions.” By that standard, Abu Ghraib, he says, was “almost Disneyesque. It’s the modern face of the Spanish Inquisition, when all humanity destructs and one can insult another just because of where they come from. It was so visually compelling.”

The intensity of his subjects matches the sophistication of his final pictures —provocative, honest, raw, and aesthetically magnetic. Viewers want to comprehend the calligraphy.

Looser calligraphy (Arabic graffiti) and abstracted figures also distinguish Alkadhi’s recent work. His earlier photo-based paintings and meticulous calligraphy were too exacting for the incomprehensible blur of casualties and atrocities in his homeland. Abstraction offers a measure of privacy, overdue consideration, even dignity.

Alkadhi, who received his MFA from New York University ITP Tisch School of the Arts, has paintings in two New York group exhibitions: Translation/Tarjama at Queens Museum of Art through September and Muslim Voices: Art & Ideas at Austrian Cultural Forum through Aug. 29. Station Museum of Contemporary Art in Houston recently included his work in Iraqi Artists in Exile.