In the pre-dawn darkness, Michele Mician met up with a group behind the Palm Springs Art Museum to tackle one of the hardest climbs in the United States. As she began the 10,000-foot ascent, the town below was so still she could hear resident owls hooting. Mician held a flashlight in hand while others steered by headlamp — their bobbing lights visible to early risers in town.

The 23 miles of trail wound relentlessly up. The sun rose, and the hills turned tangerine, pink, and blue. It looked like “God turning on the lights,” says Mician, who serves as sustainability manager for the city of Palm Springs. When her energy flagged, Mician began belting out tunes by the band Ambrosia.

“I don’t know how this whole business started …” Mician warbled.

A fellow hiker named Jason Fox chimed in “… Of you thinkin’ that I had been untrue …”

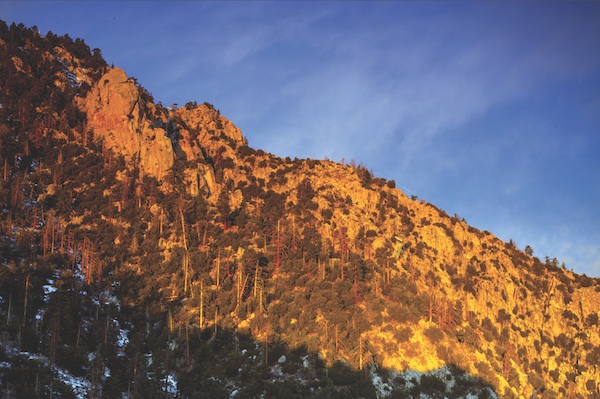

A sunrise look at Coffman's Crag. At nearly 8,000 feet up, its peak approches the altitude of the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway's Mountain Station.

Mician and Fox didn’t know each other, but they knew all the same ’80s tunes. From that moment on, they were an item. It was a meetup moment last October on the Cactus to Clouds Trail — a highly social, grueling, and somewhat underground Palm Springs experience. The C2C is adored by fitness freaks, CrossFit and boot camp trainees, and even Marines — while it’s barely recognized by local agencies and tourism officials. It lives in a netherworld between legitimacy and outlaw status, which seems to add to the appeal.

The C2C regulars hardly resemble Sierra Club hikers of old. Mician and friends wear day-glo fitness clothes. There is nary an Audubon field guide among them. Also missing: the traditional solitary communion with the wilderness. This is a chattering trail wired with Fitbits and GoPros.

At the end of the day, which for average mortals entails a full day of hiking, most hikers end up flopping down in the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway bar (which is why some refer to the trail as the “Cactus to Beer” route) for flirting, tech talk, and comparing FKTs (fastest known times). The C2C is a product of the YouTube era, where every hike is a conquest and every conquest must be posted.

The last section of the trail, called Grubbs Notch, is one of the steepest.

Some can’t stop at a single C2C and instead do a C2C2C (up and down and up). Brett Maune, a laser physicist and speed-hiker from L.A., set the Skyline record in 2 hours, 14 minutes.

A word on nomenclature: The Skyline is technically the portion of the trail from the Palm Springs trailheads to the tram’s Mountain Station. It’s roughly 10 miles with an 8,000-foot ascent. The C2C adds to the climb, rising to the 10,834-foot peak with a return ride down the tram, for a total of 23 miles and a 10,000-foot rise. But we’ll use the terms interchangeably here, as many do.

No wonder tourism officials don’t know what to do with the C2C. There’s never been a beast quite like this in the history of outdoor recreation. “It’s an interesting animal,” says Trail Discovery hiking guide Scott Scott.

Trememdous views and spectacular colors abound during the hike.

Some say it’s harder than the venerable Mount Whitney climb, and it’s been likened to hiking from Everest base camp to the summit. The bootleg trail passes through lands managed by the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service, and San Jacinto State Park. But none of these agencies manages the trail as a whole or issues permits, as the Forest Service does on Mount Whitney.

The makeshift management committee includes C2C devotees Scott, Andy Hollinger, Doreen Sabia (“The Skyline Queen”), Steve Irvin, and others. Concerned about novices getting hurt, the self-appointed caretakers erected a warning sign at the 1,800-foot level. (It was eventually torn down.) The unofficial trail crew trims cat’s claw, scrubs graffiti, and stocks two emergency rescue boxes along the route. “We do what we can because we love that mountain. We love that trail so much,” Scott says.

The managers communicate via an entertaining online message board (www.mtsanjacinto.info), where hikers check in with colorful nicknames: Zippety Dude, Screerider, and Neverwashasbeen. A favorite pastime on the board is warning newcomers how many ways there are to die up there.

In fact, people do die on the C2C. While climbers succumb to greater altitude on Mount Whitney, the C2C offers up extreme heat for much of the year. Hikers who make the mistake of turning around may seal their fate. When they reverse course, they’re descending into the cauldron of the valley floor. In winter, icy chutes are another danger. A guide for a local tour company slipped on ice and was killed on his first try at Skyline in 2004.

A close-up view of Coffman's Crag as seen from the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway.

Whether you start from the trail behind the Palm Springs Art Museum or at the west end of Ramon Road, you begin the march on the desert floor, with no shade and no water. You glimpse into the depths of Tachevah and Tahquitz canyons. Higher elevations take you through a miniature forest of chinquapin and ribbonwood. At around 6,500 feet, you walk among the gorgeous granite pillars we see shining from the valley. Along the way to the peak are well-known landmarks like Rescue 1 and 2, 5K Ridge, Flat Rock, and Coffman’s Crag (turn left here or you can get lost in Chino Canyon).

Along with the shared lingo, hikers have private names for special places on the route. Sabia has her Enchanted Garden (a yucca grove at 4,000 feet). Hollinger has his Dark Forest. Even in a high-tech, GoPro world, the C2C remains, for some, an old-fashioned rite of passage, sprinkled with personal symbolism.

Hollinger grew up in Palm Springs (his father was a founder of the Palm Springs Mounted Police) and remembers climbing to the 4,000-foot level of what is now Skyline as a teenager. There was no C2C then, just a patchwork of Indian hunting trails and bighorn tracks. Above 4,000 feet, the bighorn fade out and deer paths take over.

Hollinger often discovers shed antlers near the trail.

In an earlier era of more contemplative hiking, there was no reason to jam a hard route straight to the top of the mountain. Then came the extreme sports craze of the ’80s and ’90s; difficulty itself became desirable. In 2005, Backpacker magazine deemed the C2C one of “America’s Hardest Hikes.”

The South Palm Canyon area of Palm Springs is visible from the Cactus to Clouds Trail.

The C2C claims the greatest elevation gain of any hike in the U.S. and therefore became a coveted challenge. As more people tramped the old deer paths, the trail we know today took on definition. The last mile or two remained indistinct for a long time, however, and Sierra Club members placed yellow metal tags on the trees to guide those who wandered off course.

Hollinger, a retired volleyball coach and teacher at Palm Springs High School, has now made 215 ascents, carrying his own C2C brew in a CamelBak: glacial salt, sea salt, organic honey, and Meyer lemon mixed with water. He now sometimes sees 100 people on the trail that once hosted just a boy and the bighorn.

Before it became popular, the route was off the printed maps, and in some cases it still is. If you call the Mount San Jacinto State Park office, the person who answers the phone will tell you there is no official trail. “It’s undesignated,” office assistant Franceen Unwin says. “We encourage people not to hike it. Half the rescues out of our office generate from that trail.”

While some agencies might prefer to stuff the problematic trail under the rug, hiking guide Scott points out it’s too late for that. “The cat’s out of the bag,” he says. “It’s not going away.” Agencies and tourism officials now have a choice: Restrict access to the challenging route or go the other direction and promote it as a highlight of a Palm Springs vacation.

THikers often set out before sunrise to beat the heat and gain spectacular views of the Coachella Valley and Salton Sea.

At Mount Whitney — the closest comparison to the C2C — they’ve gone the promo route. Whitney has become a mini-industry with T-shirts, guidebooks, motel specials, and a permit system that limits users. The same could be true of the C2C one day. “It’s a feather in the hat for Palm Springs tourism,” says Matt Jordon, owner of Stout Adventures and a volunteer with the Riverside Mountain Rescue Unit. “It’s another thing for people to do besides drink martinis and flop around in the pool.”

Ownership of the trail lands might be changing: The BLM is considering a land exchange with the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians that would put portions of the trail under control of the tribe. While some hikers assume that this might limit access, the tribe has stated that trail maintenance and access will stay the same.

Some frequent users, such as Sabia, would rather the route be restricted. On a recent visit to her beloved trail, she found someone had drawn flowers in purple, orange, blue, and yellow all over the rocks. “It made me so mad and so sick,” she says. Shortcutting speed-hikers are eroding her switchbacks and tourists are defacing her Enchanted Garden.

Given the lack of supervision, along with the trail’s popularity, Sabia concludes: “It needs to be controlled.”

Sabia made her first trip 15 years ago as a purely physical challenge. But after completing 300 ascents, she’s ditched the conquest mode completely. She bows to the trail at the end of each climb and speaks of the C2C as female. “Let’s continue to take care of her and teach those who come behind us to regard her with respect,” she recently reminded her fellow makeshift managers on the message board. “She will change your life.”

C2C hikers (from left): Andy Hollinger, Doreen Sabia, and Scott Scott.

If You Go

Before donning your hiking boots and heading off to new heights, be sure you’re well-prepared. Here are a few things to keep in mind.

1. GET IN SHAPE. As you would for an expedition, doing a series of tough hikes (3,000-5,000 feet gain and loss) at least a month or two prior to your ascent.

2. ON YOUR FIRST ATTEMPT, go with someone who’s made the hike before. “The route is not always obvious, and taking an unintended shortcut can drain energy you’ll need for the last, most difficult section,” says hiking guide Scott Scott.

3. TIMING IS EVERYTHING. To avoid extreme heat below and icy conditions above, check the Mount San Jacinto message board (www.mtsanjacinto.info) for current conditions.

4. SCOTT RECOMMENDS carrying at least 3 quarts of water, along with some form of electrolytes.

5. BE SAFE. Learn from the mistakes others have made. Read about rescues and near-disasters on the Mount San Jacinto message board. The message board regulars are your best coaches for a safe trip.

— Ann Japenga