On a postcard-perfect April day in 1961, W. Clarke Swanson, former president of the eponymous frozen food company, died at age 52 of a cerebral hemorrhage. Part of a golf foursome that included former U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Swanson collapsed on the sixth green of the Thunderbird Country Club, just a few hundred feet from his home.

Swanson’s widow was certain that if there had been a hospital nearby in the mid-valley, her husband’s life might have been saved. Her conviction set in motion a chain of events that created Eisenhower Medical Center, which opened in 1971.

Fast-forward to 2014. During a diagnostic workup for an entirely different health issue, Eisenhower doctors detected an aneurysm in the brain of Swanson’s daughter, Carol Price. Left untreated, it could have ruptured, ending her life as abruptly as her father’s. But with the state-of-the-art resources available at Eisenhower, the problem was quickly resolved with an advanced, minimally invasive procedure, and Price — who currently serves on Eisenhower’s board of directors — is fine today.

This extraordinary success story of the Eisenhower Medical Center underscores the truth of Margaret Mead’s reminder to “never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world.”

rendering courtesy of eisenhower medical center

Architect’s rendering of Eisenhower Medical Center.

The Early Days: Rallying Friends to the Cause

“My mother did not waste a minute,” recalls Price, referring to the initiative her mother was driven to launch after W. Clarke Swanson’s death.

Determined to see a hospital built in the mid-valley, Florence Swanson enlisted Bob and Dolores Hope to rally to the cause a roster of influential friends that reads like a who’s who from the worlds of entertainment, business, humanitarianism, and politics. Ambassador and Mrs. Walter H. Annenberg. Peter Kiewit. Paul Jenkins. Willard Keith. John Curci. Freeman Gosden. Ernie Dunlevie. Justin Dart. Leonard Firestone.

The vision was simple.

photo courtesy of palm springs life archives

Architect Edward Durell Stone, Dolores Hope, and former President Dwight Eisenhower.

“What we really wanted was a hospital that was a West Coast version of Mayo and Hopkins,” Dolores Hope recalled in a 2001 interview.

And they set about making it happen by raising private funds to build it.

The hospital-to-be was incorporated in 1965, with Dolores Hope named president of the founding board of trustees, and achieved some major milestones in quick succession. The Palm Springs Desert Classic golf tournament, renamed the Bob Hope Desert Classic in 1965, earmarked 70 percent of its earnings to help finance construction.

In 1966, the Hopes donated 80 acres of land in Rancho Mirage as a site for the new facility. In 1967, renowned architect Edward Durell Stone, who designed the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., came on board for the project.

President and Mrs. Dwight D. Eisenhower, residents of Eldorado Country Club, agreed to name the hospital for the former president, who confided to his friend Walter Annenberg, “I must tell you that it is the greatest honor I have ever received to have a medical center named after me.”

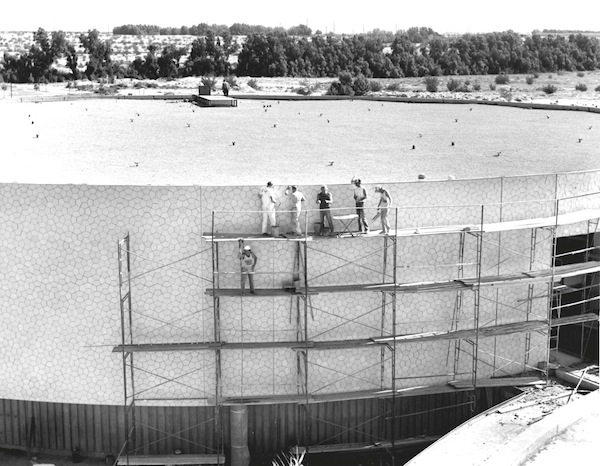

photo courtesy of eisenhower medical center

The new medical center in Rancho Mirage under construction.

Celebrity-fueled Fundraising

In November 1969, Bob Hope emceed the groundbreaking ceremony for Eisenhower Medical Center, attended by more than 4,000 people, including Governor Ronald and Nancy Reagan. Sadly, Eisenhower himself didn’t live to see it; he died a few months earlier, at age 78, of heart disease.

Two months after the groundbreaking, Dolores Hope spearheaded establishment of the Eisenhower Auxiliary, a then-women-only volunteer group that became the driving force behind fundraising initiatives such as the annual “Voices of Christmas” black-tie dinner and Eisenhower’s Collector’s Corner resale shop.

Other fundraising efforts included swanky affairs at New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel — chaired by Mrs. Astor herself — and in Paris and Los Angeles, each raising close to $2 million. The Thunderbird, Eldorado, and Tamarisk country clubs hosted annual events that also netted seven-figure proceeds.

photo courtesy of palm springs life archives

Governor Ronald Reagan, Dolores Hope, Edgar Eisenhower, and Bob Hope break ground.

The Hopes’ stature in the entertainment industry attracted other celebrities to the cause. Frank Sinatra, George Burns, Bing Crosby, and Lucille Ball contributed their talents and resources to fundraising events, bringing in additional millions.

The heady momentum of the early years was almost derailed, however, when some members of the board insisted on a study of the feasibility of adding hospital beds in the desert. Produced by the Stanford Research Institute, the study said that the Coachella Valley’s population wouldn’t need more than 50 additional hospital beds by 1980.

photo courtesy of eisenhower medical center

An aerial view of the center under construction..

“I was terribly down,” said Dolores Hope in a 2001 interview. “I said [to Bob], ‘Well, it looks like we’re out of business.’ He never did say much without thinking a lot, and then he said, ‘We’re going to build a hospital.’”

photo courtesy of eisenhower medical center

(From left) John Sinn, Betty Ford, and Leonard Firestone at the groundbreaking of the Betty Ford Center.

The Hospital Opens its Doors

In November 1971, President Richard Nixon dedicated the 138-bed Eisenhower Memorial Hospital in a ceremony before 15,000 invited guests. The next month, the hospital, with a staff of 20 physicians and 225 employees, admitted its first patient.

Fueled by philanthropy, the hospital continued to grow during the ’70s in order to meet the demand for services and have enough staff to provide them. In 1973, Vice President Spiro T. Agnew dedicated the Probst Professional Building, donated by Mr. and Mrs. Walter F. Probst.

photo courtesy of eisenhower medical center

Construction of the Annenberg Center.

In 1975, the 43,000-square-foot Kiewit Professional Building opened, donated by Mr. and Mrs. Peter Kiewit. In 1978, the 47-bed Mamie Eisenhower (east wing) addition was dedicated in its namesake’s presence by Governor Edmund G. Brown Jr. In 1979, former President Gerald Ford dedicated the Wright Professional Building, with a portion of its cost donated by Mrs. Harold (Hazel) Wright in her late husband’s memory. That same year, movie producer Hal Wallis donated $1.2 million for a medical building.

Clinical milestones during the hospital’s first decade included the opening of Eisenhower’s nuclear medicine department, arthritis clinic, and diabetes program; acquisition of new technology, including ultrasound and the valley’s first whole-body CT scanner; introduction of open-heart surgery; and launch of a cardiac rehabilitation program.

photo courtesy of eisenhower medical center

Lee and Walter Annenberg at the opening of the Annenberg Center for Health Sciences, 1981.

By the early ’70s, the auxiliary had attracted nearly 1,500 members. In 1974, then-auxiliary President Millie Gonyea presided over publication of the cookbook Five-Star Favorites: Recipes from the Friends of Mamie and Dwight D. Eisenhower. A compilation of 400 recipes culled from nearly 1,600 submissions and tested by auxiliary volunteers, it sold out immediately, raising more than $100,000 for the hospital.

The decade closed with a philanthropic bang, as Ambassador and Mrs. Walter Annenberg donated $4 million for construction of the Annenberg Center for Health Sciences on the Eisenhower campus. It was the largest single donation the hospital had received.

photo courtesy of eisenhower medical center

Eisenhower Medical Center.

The 1980s: Expanding Clinical Capabilities

Philanthropy in the hospital’s second decade was no less remarkable. Sammy Davis Jr. gave a concert that raised $1.2 million to establish the Bob and Dolores Hope chair in medical education at the Annenberg Center for Health Sciences, which opened in 1981. Mr. and Mrs. Gene Autry donated $5 million for a 100-bed expansion of the Autry Tower. George Burns, still spry at 89, headlined an event that raised $2.25 million for the hospital.

A highlight of the 1980s was the opening of the Betty Ford Center for addiction treatment, as well as the Barbara Sinatra Children’s Center for young victims of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. While the celebrity of the founders attracted attention, it was the barrier-breaking candor with which they spoke out about addiction and child abuse that positioned these facilities — and Eisenhower — as leaders in their fields.

In addition, as healthcare delivery began to shift from inpatient to outpatient settings, Eisenhower opened its Immediate Care Centers in La Quinta and Cathedral City in 1985 and 1986, respectively, and the Dolores Hope Outpatient Care Center in 1988.

This decade also saw the hospital’s cancer care program earn national accreditation, its emergency department expand to handle increasing demand, and installation of the valley’s first magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) system.

The 1990s: Developing Centers of Excellence

In this decade the hospital’s clinical talent was geared toward Centers of Excellence, focused largely on diseases associated with aging; notably, 70 percent of Eisenhower’s patient population is covered by Medicare. Emphasized specialties included orthopedics, cardiology, and cancer.

The hospital also marked some significant medical milestones. In 1990, cardiac surgeons performed their 3,000th open-heart procedure. Brand-new cardiac catheterization labs opened in 1994. In 1997, Eisenhower became the first Coachella Valley hospital to offer trans-radial coronary stenting to treat blocked arteries, as well as electrophysiology procedures for diagnosing and treating certain heart rhythm irregularities.

By 1995, the Bob Hope Chrysler Classic had raised almost $18 million for Eisenhower over 35 years. The auxiliary had contributed nearly $15 million since its inception 25 years prior. By the close of the ’90s, however, there was trouble in paradise.

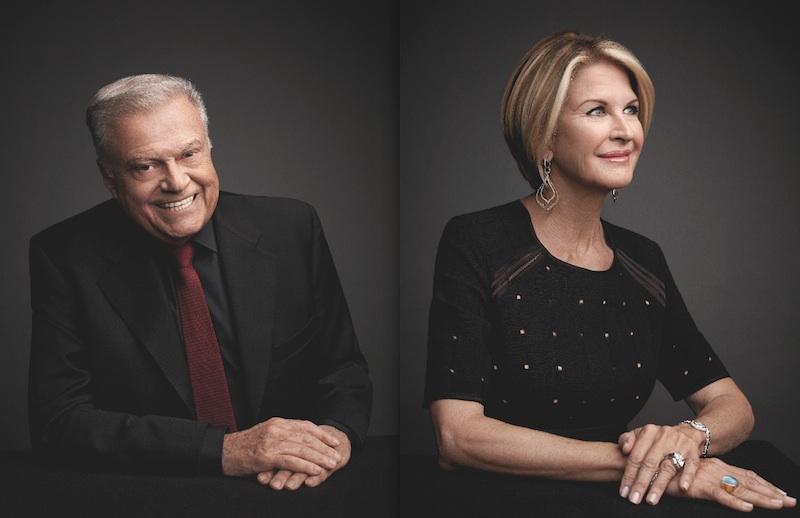

photos by art streiber

Harold Matzner and Suzy Leprino, members of Eisenhower Medical Center Board of Trustees.

The New Century: A Time of Tremendous Transition

“The prominent families who started Eisenhower in the ’60s had envisioned a hospital that people with high expectations felt safe and comfortable coming to for care,” says G. Aubrey Serfling, who became Eisenhower’s president and CEO in early 2000.

But by the time he arrived, he admits, that vision had dimmed. Eisenhower had “slipped into complacency and our contributors … had lost confidence because our service wasn’t where it should be,” he says.

Serfling set about making changes, starting with an organization-wide Performance Excellence program, mandatory for all employees, based on the Disney Institute’s model for superior customer service. The initiative was supported by a donation from the late Lois Horvitz, a longtime Eisenhower trustee.

Serfling built a new management team. “I needed strivers,” he says. “Coming from Midtown in Manhattan, I was used to a level of energy and drive that was a long way from what was going on here.”

And he told the board of directors, “We need to rededicate ourselves to the founders’ vision of excellence. It will take a lot of effort and money. I’m up for it — are you?”

Campaign Eisenhower: “Unprecedented” Fundraising

Led by Chairman Harry Goldstein, the board responded by approving a $250 million capital expansion and renovation to meet the Coachella Valley’s growing needs. In fact, by 2000, the valley’s year-round population had more than tripled from when the hospital first opened — disproving the earlier Stanford predictions about the desert’s demand for hospital beds.

“The way in which we gathered support for our hospital, philanthropically, was unprecedented,” Goldstein says, referring to the ensuing fundraising effort, named Campaign Eisenhower. So were the results.

Campaign Eisenhower raised $300 million, jump-started with a $25 million gift from the Annenberg Foundation — then the largest single charitable donation in Coachella Valley history.

The total given by the Annenbergs alone over the years is difficult to grasp: $123 million.

“It’s quite amazing what Mr. Annenberg did,” says Joel Hirschberg, a board-certified internist and rheumatologist who’s practiced at Eisenhower since 1981, caring for many of the hospital’s major donors. “When (Annenberg) asked his friend Dwight Eisenhower to lend his name to the new hospital, he promised him that he’d always look after it. That’s in part why the Annenbergs were so philanthropically involved with the medical center over the years; they kept that promise.”

Their largesse enabled Eisenhower to build what’s now called the Annenberg Pavilion, a 280-bed, seismically sound, technologically advanced hospital building with an all-new intensive care unit and dedicated orthopedic and neurology floors.

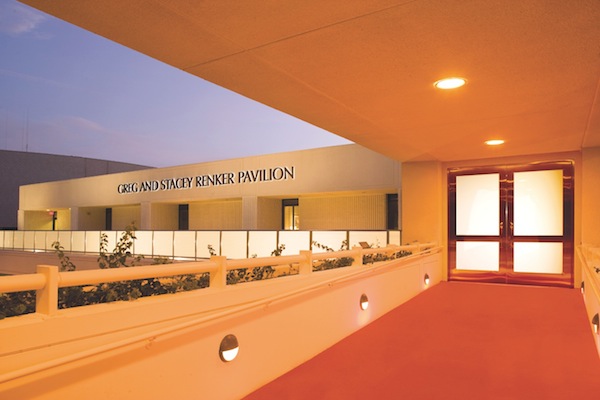

“But the entire community responded to Campaign Eisenhower,” adds Michael Landes, who came on board as president of the Eisenhower Medical Center Foundation, the medical center’s fundraising arm, in 2002. “With those monies, by 2008 we established the Lucy Curci Cancer Center, built a new imaging center and cardiac cath lab, doubled the size of the Tennity Emergency Department, completed the all-suites Renker Pavilion, expanded the orthopedics practice, and built a brand-new self-generating energy plant.”

photo by taili song roth

Eisenhower Medical Center Executive Leadership Team. From right, Alan Williamson, V.P., Medical Affairs, Martin Massiello, executive V.P. and chief operating officer, Ann Mostofi, V.P., Patient Care/CNO, Michael Landes, president, Foundation, and Aubrey Serfling, president/CEO..

Revitalized Medical Center Earns National Recognition

The reenergized medical center began racking up national recognition for its clinical and service excellence, including being named one of the country’s top 100 hospitals for its quality of care, operational efficacy, and financial performance. Eisenhower also was designated a Magnet® hospital for its nursing excellence and outstanding patient care, a distinction that only 7 percent of U.S. hospitals achieve.

In 2008, Eisenhower began what is arguably its greatest transition: from community to teaching hospital. Once again, philanthropy made it possible. Today Eisenhower is the first hospital in the valley to offer an accredited residency program and now has a full complement of 56 physicians-in-training in internal medicine and family medicine.

In addition, Eisenhower has grown from a local hospital serving the mid-valley into a health system with a network of clinics from Palm Springs to La Quinta. One jewel in this crown is the three-story, 90,000-square-foot La Quinta health center named for benefactors George and Julia Argyros.

A Growing List of Supporters

“Three more country clubs — Bighorn, The Reserve, and The Vintage — have become involved in raising significant funds for Eisenhower,” Landes says. “More than 11 golf tournaments around the valley contribute proceeds to us. And we have over 400 couples and individuals who each have donated $250,000 or more; of these, more than 112 are members of the prestigious Ambassador Society, donors who’ve cumulatively given Eisenhower $1 million or more.”

Recently, he notes, the hospital needed to quickly raise $25 million to make its original Edward Durell Stone–designed building more seismically secure. “Thanks to Dennis and Phyllis Washington, who committed $12.5 million, “ Landes says, “and our trustees and loyal donors, we raised the funds we needed in 14 months.”

But it’s not only the über-wealthy who contribute to Eisenhower.

“We’re fortunate to have over 1,300 families who give us $1,000 a year or more through our annual fund, raising over $2.5 million annually,” Landes points out. “Plus, the auxiliary has raised over $18 million to date and more than 800 volunteers have donated five million hours of time. They’re an integral part of the structure of this hospital.”

photo courtesy of eisenhower medical center

The entrance to the Greg and Stacey Renker Pavilion.

What Motivates Donors

“We’re lucky to have a sophisticated board, many members of which also sit on boards of renowned medical institutions around the United States,” says Serfling.

“We don’t want to be ordinary; we want to be excellent — and they know we can’t do it on patient-care dollars alone. They see what it takes, and that motivates them because they want this level of care for themselves. I tell them not to be ashamed of that, because it benefits everyone who walks through our door.”

Greg Renker, co-founder of the Guthy-Renker direct marketing juggernaut and current chairman of Eisenhower’s board of directors, is a case in point.

“I’m a grateful patient,” he says. “At 41, shortly after I joined the board over 20 years ago, I had an emergency heart bypass that saved my life. Then about three years later, my wife, Stacey, contracted streptococcal toxic shock; 66 percent of people who contract this are dead in 48 hours. Eisenhower saved both our lives.

“I obviously had a what-can-I-do-to-thank-you response,” he continues. That translated into gifts that helped establish the Renker Wellness Center and the 24-room Greg and Stacey Renker Pavilion, which epitomizes the hospital’s commitment to offer “a healing environment like no other.”

“To the degree we can give tools to deliver that kind of care to others, that’s pretty rewarding,” Renker adds.

Carol Price, whose father’s death was the catalyst for creating Eisenhower Medical Center, says she and her husband, Charlie, were “proud to accept the mantle [from the hospital’s early supporters] to help Eisenhower become a true state-of-the-art medical center.” Alluding to her own experience, she adds, “Our lives and our families’ lives depend on it.”

“Eisenhower really wouldn’t be anything close to what it is today if it weren’t for the commitment to philanthropy that the board and community have had,” Serfling emphasizes. “We would have had to make a lot of compromises in our quest to do it right if we didn’t have that support.”

“This legacy of philanthropy is in the fabric of who we are, and we really do feel blessed,” Landes notes. “In this era of hospital mergers and consolidations, we wouldn’t retain our independence without it. With our donors’ support, we have some control over our destiny.

“We’re lucky,” he adds, referring to Eisenhower’s supporters then and now. “We can dream big dreams because of them — and see them come to fruition.”