111 East

ART

Editor's Note: Ed Moses passed away Jan. 17, 2018, at the age of 91.

There are two kinds of dads: those who want their sons to follow in their footsteps, and those who prefer they run in the opposite direction. Painter Ed Moses once fell into the latter category. He bristled when his son Andy decided to move in 1982 from Los Angeles to New York to pursue life as an artist. Ed, who began painting at Long Beach City College after serving as a surgical technician during World War II, hit his stride that year, with three solo and eight group exhibitions from L.A. to Japan.

Andy would go it alone.

“We were estranged for a while,” says Andy, who stayed 18 years in New York and then moved to Malibu in 2000. “But five years after [I moved] back to California, he started to connect with my work in a big way. That connection has built hugely over the past 15 years, and the relationship has come full circle. We’re very connected now. We’re neighbors. We visit each other’s studios. We talk about painting. We have dinner four times a week.” The Moseses now have neighboring houses in Venice, California.

They also gush about each other’s recent milestone exhibitions: Ed’s Moses@90 at William Turner Gallery and the adjacent Institute of Contemporary Art (formerly Santa Monica Museum of Art) and Andy Moses: A 30-Year Survey at the Barrett Art Gallery at Santa Monica College.

This month, Art Palm Springs honors Ed and Andy as artists of the year, an award previously given to Lita Albuquerque, Larry Bell, Judy Chicago, and Mel Ramos. In addition to being fêted Feb. 16–19 at the festival at Palm Springs Convention Center, Ed and Andy feature in solo installations in the booths for William Turner Gallery and Melissa Morgan Fine Art, respectively.

“We have exhibited together, but this is the first time we’re being honored together,” Andy says. “I think it’s great.”

PHOTOGRAPH BY JOYCE KIM

Andy and Ed Moses, photographed Jan. 4 at Ed’s studio in Venice, California.

Ed was struggling in his pre-med program when a friend advised him to see Pedro Miller, an art professor who could channel his restless energy. Ed plunged his hands into paint and had his way with the canvas. The instructor looked at it, then at him, put the work up for others to see, and declared, “This is an artist.”

“It changed my life,” Ed says. He eventually transferred to UCLA and met light-and- space/finish-fetish artist Craig Kauffman, who introduced him to Walter Hopps, the impresario of L.A.’s scene-setting Ferus Gallery. Hopps included Ed’s work in a 1957 group exhibition and gave him a solo show in 1958, enshrining him among the legendary Cool School artists.

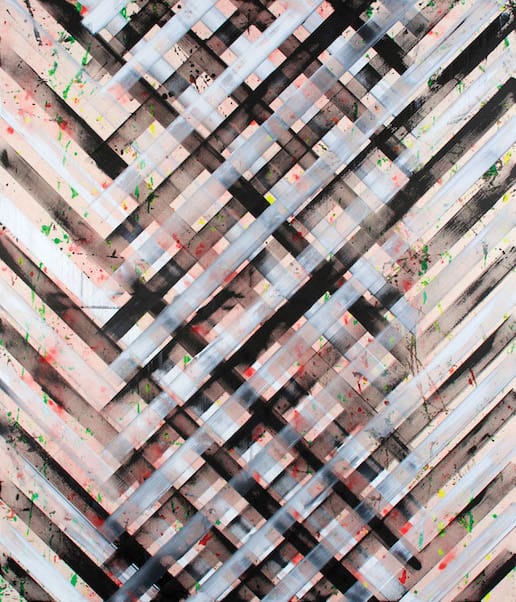

While his contemporaries worked in pop (Ed Ruscha), light and space (Kauffman, Bell, Robert Irwin), and assemblage (Ed Kienholz, Wallace Berman), Ed — whose early paintings had vacillated between exacting renderings of the Venice boardwalk and the Santa Monica Pier — preferred abstract expressionism, wild paintings with heroic gestures and wayward scribbles. In the mid-’70s he began a series of grid paintings, one of his most recognizable (and revisited) bodies of work, as well as reductive, monochromatic paintings, exhibited as recently as 2006 at the venerable Margo Leavin Gallery in L.A. Never one to settle into a particular style or aesthetic, Ed explores and responds to what he sees. His recent craquelure paintings, for example, riff on the splits and fissures of paint he saw on a Piet Mondrian canvas. “I thought, Wouldn’t it be great if I can do a whole canvas like that? And I figured out how to do it,” he says. “I like discovering, rather than painting something I have in my head. I’d rather find something out. Flop around like a fool and something might appear, by chance, and I might keep exploring it. I never know what’s going to happen.”

PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY ED MOSES/WILLIAM TURNER GALLERY

Ed Moses’ Many Feet, 2017.

Ed Moses' Gump, 2002.

Ed paints every day, undeterred by the effects of aging. Since his recent heart-valve surgery he relies on a wheelchair, but his work ethic never wavers. He has about 20 paintings in process in his outdoor studio, a courtyard flanked by barnlike structures where he stores and displays his work. The paintings contain traces of earlier work, particularly his grids and “worms.”

“They cross-pollenate, but they’re not floral,” he deadpans. “I don’t know what I’m doing. The situation calls the shots. I just respond to the circumstances.”

Andy marvels at his father’s audacity and prolific output. “He has a super-restless personality, and he follows his gut,” he says. “He’s not afraid to try anything. There’s no sense of preciousness. He can move seamlessly from one thing to another, and he hits it on the first one. It’s very impressive.”

If Ed’s work lacks preciousness, Andy delivers it in placid abstractions evoking Southern California’s dreamy sunsets, horizons, and ocean. The ethereal compositions, with iridescent, satinlike surfaces, share the sensibilities of the light-and-space and finish-fetish artists who emerged with Ed at Ferus Gallery.

Andy, who has always taken inspiration from the natural world, comes from a rigorous conceptual art background.

Andy Moses' R.A.D. 1704.

He graduated from CalArts, where he studied under Michael Asher, John Baldessari, Douglas Huebler, and Barbara Kruger. In New York he was a studio assistant for Pat Steir while also creating his own work. Within only a few years, he was showing in the city with Annina Noesi Gallery and back in L.A. with Patricia Faure Gallery.

His earliest paintings evoked the big bang or formations seen through a microscope, images he later flanked on the left and right with columns of text culled from the science section of The New York Times. “Science was one of my passions,” he says. “The words and the microscopic image reinforced and fought against each other.” In the ’90s, his imagery shifted to the cosmos, inspired by the night sky in Montauk, on the eastern tip of Long Island, where he was living.

In L.A., he was captivated by the ocean and horizon, which dominate an ongoing body of light-and-space work. The sunlight beaming into his studio also had a transformational effect on his work.

“They cross-pollenate, but they’re not floral,” Ed deadpans. “I don’t know what I’m doing. The situation calls the shots. I just respond to the circumstances.”

“It became about looking out, about perception and the sublime,” he says. “Seeing 2001: A Space Odyssey also set off the lightbulbs. That part when you’re plunging into infinity — it’s hypnotic.” In the first paintings in this series, light emanates from the horizon, and colors darken as they move away from it. One day, he leaned one of the canvases against a studio wall and noticed how the light coming through the window hit its surface.

“I began making convex paintings to [mimic] the curvature of the Earth, space, and horizon. The pearlescent [paint] changes the effect of the colors; there’s a subtle shift in color and luminosity as you move around it.”

He has since added more dynamics: serpentine lines, undulating waves, florescent color, and even faceted, six-sided canvases that have a cinematic quality. “They still create a sense of receding space,” he asserts. “Everything straightens out as you look toward the horizon.”