Early on in the movie, Glenn Close’s character — a level-headed, ambitious, talented woman — moves from a small, private East Coast school to a dumpy apartment in the Village to start her career as an aspiring writer. Conflict arises when the man she adores — also an aspiring writer — shows her his first manuscript and asks for her opinion. When she tells him it’s not very good, he has a hissy fit. Partly because it’s the truth but also because he knows right down to his calloused hunt-and-peck fingertips that she’s actually a better writer than he is. And. That. Just. Isn’t. Fair.

This scene sets up much of what follows in the movie. But it’s not a scene from Close’s latest film, The Wife. Rather it’s from her first: The World According to Garp. Close has walked miles in the sometimes uncomfortable shoes of dozens of eclectic characters (remember Alex Forrest in Fatal Attraction?) since Garp, for which she also received her first Oscar nomination in 1982, yet here she is again, having come full circle: playing an enormously talented “lady writer,” as one editor calls her, whose success is just too damn much for almost everyone in the male-dominated publishing world to swallow. Has anything changed in the last 36 years? In The Wife, Joan Castleman (Close) meets a female author (Elizabeth McGovern) who suggests she give up any dreams of being a writer.

“Don’t ever think you can get their attention,” the author warns a young Joan.

“Whose?”

“The men.”

Her words oddly echo what her publisher tells her son (Robin Williams), the other aspiring writer in the family, in Garp: “Your mother’s writing is dangerous stuff. I’m getting hate mail from a lot of men for publishing her.” As if to prove the point, minutes later some wacko with a rifle up in a tree tries to assassinate her.

• See related story: Glenn Close to Receive Icon Award at Palm Springs Film Fest.

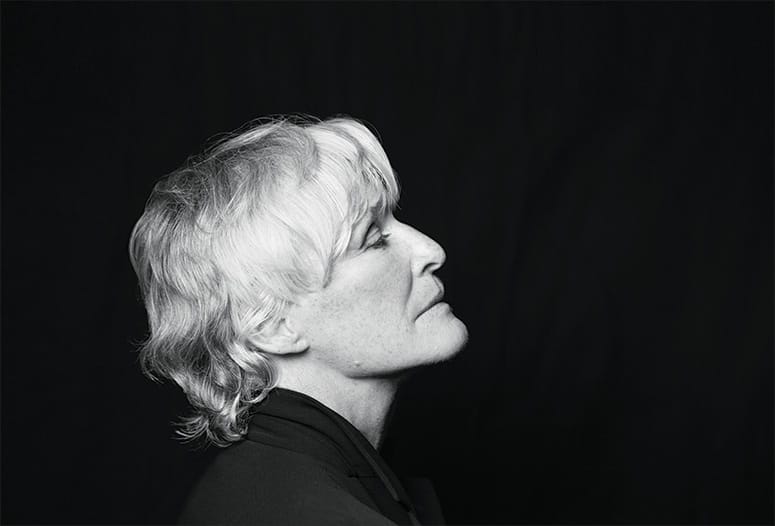

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF ALAMY

Glenn Close in The World According to Garp

Nobody tries to assassinate Close in The Wife, but her character is ignored, demeaned, belittled, and greatly underestimated. And that’s the way her husband, the illustrious writer Joseph Castleman (Jonathan Pryce) treats her. “My wife doesn’t write,” he tells a room full of his admirers after learning that he’s won the Nobel Prize in Literature. “Thank God.” When Joe wanders off to glad-hand another group of literary groupies, his wife is left in the lurch. The bright twinkling star of the evening has moved on; his coterie of literary acolytes wants to do the same.

“A pleasure, Jean,” says one, making a hasty retreat, cocktail in hand.

“It’s Joan,” she corrects as he flees.

They can’t even get her name right. Well, at least they try. When she arrives in Stockholm, where her husband is to receive his award for writing novels whose “form will challenge future novelists for decades to come,” as they tell him, Joan, lingering a few steps behind the great man, is introduced in a stentorian voice as “the wife of Joe Castleman.” To the literary illuminati, she has no name. She is, like the title of the movie, only the wife. What to do with her? A well-meaning female member of the Nobel committee suggests she might want to “go shopping” while Joe is busy with more important activities.

But as Joan herself has reminded her husband, “There’s nothing more dangerous than a writer whose feelings have been hurt.” She’s not talking about herself here, but she might as well be. Because, as we soon learn (spoiler alert), the wordsmith behind the great works that the Nobel committee has lauded for their “extraordinary intimacy about life and death” is not the preening, pompous, self-involved Joe Castleman but his shy, effacing, brilliant wife, Joan; she’s the one who, for decades, has been writing his books while getting absolutely no recognition for it, not even from him.

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF ALAMY

Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction

“When I read the script I immediately thought it was such an intriguing story,” Close says while taking a break from her latest role as the mother of Joan of Arc (more odd shoes to wear) in the New York premiere of Jane Anderson’s play Mother of the Maid (Anderson also wrote the screenplay for The Wife). The film follows the couple’s relationship from when they first meet at Smith college in 1958, where he’s a writing instructor, married, of course, who leaves his wife and child to go live with his gifted student in a seedy apartment in Greenwich Village so they both can write. He may be older (and, he thinks, wiser), but she has more talent. And so we see how that affects their relationship over the 34 years of their marriage. Clue: not well. When Joan asks him to, please, not thank her in his acceptance speech, he says, “If I don’t, I’ll come off as a narcissistic bastard.”

“But you are,” says Joan, matter-of-factly.

“Of course,” Close says, “what everyone wants to know is, why does she stay with him?”

The answer to that question, perhaps, comes in a pivotal scene early in their marriage when a young Joan (played by Close’s real-life daughter, Annie Starke) tells him his first novel isn’t very good but, “I know how to fix it … do you want me to fix it?”

She says that, Close intones, “Because she does, in fact, know how to fix his novel but also because she doesn’t want to lose him. She had that mindset that women have had for so long of, I need you in order to be me. Without knowing it, they fall into this unusual relationship as far as the work is concerned. And then it all becomes something else. At the end she realizes the cost of the lie she’s been living and she just can’t live with it anymore.”

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF ALAMY

Glenn Close in Dangerous Liaisons

For Joan, going to Stockholm with her husband becomes a voyage of self-discovery. It feels as if in each critical scene in the movie she is peeling off another layer of her life in an effort to discover who she really is. “One of my favorite scenes to shoot,” Close says, “is when she stomps out of the dinner for the Nobel recipients and goes back to her hotel room where she says she’s dying to get out of her dress. It’s a metaphor, of course. She’s really dying to get out of her old life, to shed her skin, to be herself.”

Close admits that when she first read Anderson’s script, her biggest concern was that women in the audience “would stand up on their chairs in the theater and yell, ‘Just leave the bastard!’ I needed to understand the answer to that question as an actress because I knew everyone else would be asking the same thing — why doesn’t she leave him? So Jane and Björn [Runge, the director], and I spent a good week sitting around a table talking about the character. Jane did a lot of rewriting because we needed to understand where Joan was emotionally and psychologically to understand the arc of the story.”

Harold Matzner, longtime chairman of the Palm Springs International Film Festival, which is presenting Close with the Icon Award at its annual Film Awards Gala on Jan. 3, says it’s not just women who might wonder why she stays with her self-absorbed husband. “The guy is horrible,” he says, laughing. “He is everything a man should not be to a woman. Which makes the job that Glenn did in that movie even more amazing and one of the reasons the committee chose her for the Icon Award. Having been nominated for an Oscar six times, she’s obviously an amazing actress, but this role may be the best of her career. She certainly deserves another nomination ,and I think a lot of people think she’s going to get one.”

When I ask Close why, indeed, Joan stays with her self-centered, narcissistic husband, she takes a long pause before answering. “It’s complicated. Anyone who’s been with someone for a long time knows how things change in a relationship, how it starts out one way and then evolves, over time, into something else. At first you tend to put up with certain unpleasant things and eventually those things become intolerable.”

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF SONY PICTURES CLASSIC

Glenn Close in The Wife

That doesn’t mean Joan is a fool, she says. Her character makes it clear that she has been complicit in the couple’s literary cover-up from the start and that she was doing what she always wanted to do. “Joe wanted fame and accolades, which he got. Joan just wanted to write. It was never about the fame for her.” When Joe Castleman’s ersatz biographer, Nathaniel Bone (Christian Slater), tells Joan over drinks in Stockholm that he thinks she’s the real writer in the family, not her husband, and he’s going to put that in his book, she says, “Please don’t paint me as a victim. I’m much more interesting than that.”

And she is.

“I think what’s really important for everyone to understand about this film,” says Anderson, the screenwriter, “is that it’s not about female victimhood. It’s about a very specific woman in a very specific marriage. The film is really about what we do in a marriage to make it work, as well as the various compromises we make and the contracts that exist in a relationship. I’m thrilled it’s coming out at this moment in time. Seeing Glenn Close’s performance with an audience is a very gratifying thing because of the moment we’re living in right now,” she says, alluding to the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements.

“There’s an early scene in the movie when they’re on the plane going to Stockholm and she knows he’s flirting with the airline attendant because she knows that’s how it’s been for so many years,” Close says. “She knows how he acts toward women — which is poorly, dismissively. But when she hears what the Nobel Prize Committee has to say about his writing — her writing — it’s a shock to her. You can see it on her face. That’s when it happens. That’s when she says, ‘I can’t take it anymore.’ At this point, I think she’s as angry at herself as she is with her husband. Everything is coming to a head. It’s the perfect storm.”

Close says she’s looking forward to coming back to Palm Springs to celebrate both her role in the movie and her 36 years of iconic roles in film, from Garp and The Big Chill to Fatal Attraction and Dangerous Liaisons. “I remember getting together in Palm Springs with a group of friends years ago and renting a house over Thanksgiving and how beautiful the light was against the mountains while we were enjoying a wonderful dinner outside under these beautiful trees on the patio at Le Vallauris — in November!”

Matzner recalls spending time with Close after her performance in Albert Nobbs, which also earned her an Academy Award nomination and the Career Achievement Award at the Palm Springs International Film Festival in 2012. “She was phenomenal. Here you’ve got one of America’s greatest actresses and she could not have been more gracious and accommodating than she was. It’s really nice to have her back. It’s like having an old friend, a very talented friend, return after you haven’t seen them for a few years. And, honestly, I think she’s just a very remarkable woman.”

As are her characters. Even if the men don’t always think so.