She stepped in to do Lena Horne’s hair on set of the 1943 film Stormy Weather when the studio hairdresser refused to work on a black woman, and the star became her lifelong friend thereafter. She set bridal trends for generations to come with her long-sleeved lace creation for Grace Kelly’s 1956 wedding to Prince Rainier. And she designed the sultry white crepe halter dress worn by Elizabeth Taylor in 1958’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof that sold hundreds of thousands of copies at retail.

Though Helen Rose may not be a household name like her contemporary Edith Head, she was a costume design legend in her own right who was able to parlay a feathers and froufrou beginning, making burlesque and Ice Follies costumes, into a glittering Hollywood studio film career.

• See related story: We profile four young Hollywood actresses who bring Helen Rose's costumes to life.

A two-time Oscar winner, she headed the costume department at MGM between 1949 and 1966, designing for more than 200 films. Rose earned a reputation for having a way with chiffon, creating romantic, “dancing look” dresses (as Palm Springs Life once described them) for the most beautiful women in the world, including Judy Garland, Esther Williams, Lana Turner, Cyd Charisse, and Debbie Reynolds.

“It’s true that Edith Head’s story was exceptional and that she controlled her own narrative,” says costume historian Deborah Nadoolman Landis, founding director of the David C. Copley Center for Costume Design at UCLA. “But she also started in the 1920s at Paramount assisting Howard Greer and Travis Banton designing for Clara Bow. Rose was designing the Ice Follies. There was no studio marketing machine promoting Rose’s work — not until much, much later.”

Dolores Gray, Helen Rose, and Lauren Bacall in Designing Woman (1957).

PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF MARGARET HERRICK LIBRARY, ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES, WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT INC., ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

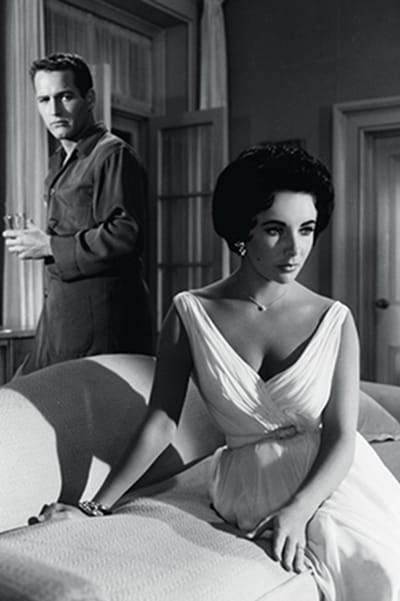

A production still from the film Cat on a Hot Tin Roof featuring Paul Newman and Elizabeth Taylor.

Still, Rose managed to design some remarkable work, including Betty Hutton’s spirited Western wear in Annie Get Your Gun (1950), Anne Francis’ genre-defining mini-dresses from sci-fi classic Forbidden Planet, which were ahead of their time in 1956, and Taylor’s sexy slip from Butterfield 8 (1960).

In an age when women looked to the big screen for fashion ideas, she offered enduring inspiration for lingerie as outerwear, chiffon ball dresses, and classic wedding attire, because when MGM’s Hollywood starlets decided to marry, Rose was the go-to to throw showers and design their wedding gowns, which were gifted from the studio as part of the publicity machine.

“I was never subservient to the stars, nor was I in awe of them,” Rose wrote in her 1976 autobiography, Just Make Them Beautiful. “I treated them as I would all other girls, especially if they were young. I understood their problems, and they knew I was their friend as they were mine.”

When the studio system started to wind down, with directors increasingly turning to store-bought wardrobe, Rose found a second career in fashion, designing her namesake collection from 1957 to 1972. She retired to the desert in 1970 and was a mainstay on the charity fashion show circuit, raising money for local hospitals by showing her collection and archival costumes (and providing live commentary) alongside Don Loper, Ernest Newman, and other designers.

Rose designed this gown for Cyd Charisse in Silk Stockings (1957). The gown is constructed of beige and white chiffon, accented with a rhinestone brooch. Like Rose, Charisse and husband Tony Martin lived in Palm Springs for many years.

PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ALAMY

Rose’s dress for Elizabeth Taylor in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958).

“Many fashion models would consent to return to do some of my fashion shows,” she wrote of her recurring events at Palm Springs Racquet Club. “I did always depend on Barbara Marx [Mrs. Frank Sinatra] and Nelda Linsk [Mrs. Joe Linsk] to lend their beauty and style to my fashion runway.”

Upon her death in 1985, she bequeathed her precious few archives (the studio owned and sold almost everything), which also include a couple of choice costumes made by fellow designers Adrian and Cecil Beaton, to local Palm Springs modeling agent Marilyn Visel and her business partner Barbara Marx (no relation to Mrs. Sinatra). In 2011, Marx gave them to the Palm Springs Historical Society, which stores the treasures in a climate-controlled vault.

The dresses were last seen in public in 2015 during a fashion show at the Palm Springs Woman’s Club, when Rancho Mirage resident Bill Marx (Harpo Marx’s son and the husband of Barbara the modeling agent) remembers being at the piano to accompany the cat-walkers. “These costumes were made for people like Lana Turner and Elizabeth Taylor, who were so much smaller,” Marx says. “The models really had to work at getting these things on, not like they had girth on them at all; it’s just that it was a different time.”

Rose’s down-to-earth, Midwestern charm made her an easy confidante to Hollywood royalty and helped propel her success. She was born in Chicago to middle-class parents; her father, William Bromberg, was part owner of an art reproduction company, and mother Ray Bobbs was a seamstress. After attending the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, Rose got her start designing burlesque costumes for 37.5 cents an hour, then followed her parents out West after the stock market crash of 1929.

Rose’s costume design drawing for The Last Time I Saw Paris (1954) depicts a dress for Elizabeth Taylor as the character Helen Ellswirth.

PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF MARGARET HERRICK LIBRARY, ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES, WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT INC., ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

She married Harry Rose in 1930 in Los Angeles and began working for sister-and-brother producing team Fanchon and Marco, designing costumes for low-budget stage shows. Mae West was the most famous star she worked with during that time in the late 1930s, and in her autobiography, she remembers being impressed by the muscle men in West’s act. After Rose complimented the blonde venus on her hunky co-stars, West quipped, “I handpicked every single one myself!”

Rose then had a brief stint at 20th Century Fox, where she was assigned to design the costumes for the 1943 film Stormy Weather, the first all-black studio musical, staring Louis Armstrong and Horne, “who was being treated with very little tolerance and respect,” Rose remembered. “She was beautiful, talented, elegant, and intelligent, but a black woman was still not considered acceptable in Hollywood in the 1940s.” When a hairdresser said it was against union rules to work on Horne, “I blew up, I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Lena really cemented our friendship forever at that point for she never lost her composure. She just sat quietly, never saying a word, behaving like the lady she is.” The incident was holding up production, so Rose did Horne’s hair herself.

Then Louis B. Mayer came calling, hiring Rose to work at MGM under supervising costume designer Irene Gibbons. Their relationship was rocky at best, with Gibbons sidelining her protégé, until Rose reconnected with Horne, by then a big star, who helped recruit her to design some costumes for her 1945 film Ziegfield Follies, giving the young designer the vote of confidence she needed to go from shrinking violet to full-blown Rose.

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF MARGARET HERRICK LIBRARY, ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES, WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT INC., ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Fred Astaire and Cyd Charisse in Silk Stockings (1957).

In the 1950s, she was instrumental in helping to create the on-screen glamour of Taylor, Kelly, and Turner, giving them a softly sensual look that resonated with the era’s happy homemakers. For the 1952 MGM movie The Merry Widow, Rose put Turner in a waist-cinching feather corset that became so popular with lingerie manufacturers, they started calling it a merry widow.

One of the pieces in the Palm Springs Historical Society’s Helen Rose collection is a short pink organdy chiffon wedding dress with appliqued and embroidered flowers that she designed for Kelly’s 1956 film High Society. The star liked the dress so much that it inspired her real-life bridesmaids’ dresses. How Rose came to design Kelly’s highly publicized wedding dress is another story.

In 1956, she had already designed ensembles in four films for the young actress with patrician charm. Kelly had been cast, with James Stewart, in Designing Woman, a “clothes film” with a number of costume changes, according to Rose’s biography, that was partially inspired by the designer’s own story. However, when Kelly returned from holiday with her family, before shooting was to begin, she asked for a meeting with her costume guru to convey some news both good and bad. The good news? She was to marry Prince Rainier and become “Her Most Serene Highness, Princess Grace of Monaco.” The bad? High Society was to be her last role, not Designing Woman.

The studio negotiated to film the event so audiences around the world could watch and offered to make the wedding gown, which took 30 seamstresses, 300 yards of antique lace that cost $2,500, and 150 yards of taffeta, tulle, and silk. The classic, long-sleeved design influenced generations of brides, including Catherine Middleton, whose Sarah Burton for Alexander McQueen gown channeled Rose’s Hollywood princess.

“No studio designer had ever been asked to do anything like this, and I knew the eyes of the entire world would be on me and the MGM wardrobe department,” Rose said in Jay Jorgensen and Donald L. Scoggins’ 2015 book on the history of costume design, Creating the Illusion. In Rose’s biography, Kelly said, “I explained to Helen the kind of line and look I wanted, with gros de longe skirt and lace blouse, and as usual, she came up with something that surpassed my imagination and hopes. She found an old Rose Point lace shawl for the blouse, which was a dream, and then re-embroidered pearls over the entire thing; a real work of art.”

“It’s the level of detail, the antique lace accented with pearls and added lace pieces to make it three-dimensional that has made the bridal gown stand the test of time,” says Kristina Haugland, curator of costume and textiles at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, to which Kelly donated her gown. “It’s one of our most beloved objects,” she says of the fashion relic, which is too fragile to have on permanent display.

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF ALAMY

Helen Rose, Cyd Charisse, and Joe Pasternak, Hermes Pan on the set of Meet Me in Las Vegas (1956).

Another piece in the Palm Springs Historical Society’s collection is the famed Maggie the Cat dress worn by Taylor. By the time of the 1958 film, Rose and Taylor already had a long working relationship; for her marriage to Conrad Nicky Hilton, Taylor even designed a version of the dress Rose had made for her in Father of the Bride (1950).

“Cat on a Hot Tin Roof was not exactly a designer’s dream,” Rose said in Creating the Illusion. “There were only three changes of wardrobe in the entire picture; a slip, a skirt and blouse, and a short, simple afternoon frock, which was worn throughout the rest of the film.”

Rose spent $2,000 creating the perfect slinky pink satin and lace slip, which helped establish the trend of underwear as outerwear, but the white shirtwaist dress she originally created as the afternoon frock was dismissed out of hand by Taylor, who by then was with Mike Todd, as too dowdy. As an alternative, the costume designer showed her a sketch of the deep V-neck and wide-belt look, with a draped Grecian bodice, and she approved. The crew worked all night to get it ready for shooting the next morning.

The designer put the style in her first retail collection, which was sold at I Magnin, Bonwit Teller, and other department stores. They sold thousands of them at $250 each to women who wanted to emulate Taylor’s curves. The Cat dress, as it was known, was such a sensation that Rose kept it in her line for three years, summing up the appeal of her lifelong work this way: “I found women the world over were always eager to wear a style worn by a star in film.”