Actor Tom Neal wanted to be famous in the worst way. And that's pretty much how he did it.

By Arthur Lyons

Actor Tom Neal wanted to be a star in Hollywood. He hardly came close.

Although he was featured in at least 180 Hollywood productions, starting with Out West With the Hardys in 1938, he never really emerged from B-movies. Indeed, he spent virtually all of his career playing macho character roles in films such as Flying Tigers, Behind the Rising Sun and First Yank Into Tokyo.

Although he was featured in at least 180 Hollywood productions, starting with Out West With the Hardys in 1938, he never really emerged from B-movies. Indeed, he spent virtually all of his career playing macho character roles in films such as Flying Tigers, Behind the Rising Sun and First Yank Into Tokyo.

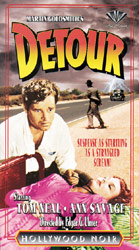

The closest he got to bigtime fame was his role as the unlucky, star-crossed piano player Al Roberts in the cheapie 1945 noir classic Detour. In that film Neal's character hitches a ride to California to be with his girlfriend, accidentally kills two people and ends up destitute and on the lam. In the last reel, as he is being shoveled into the back of a police car, he intones the classic line: "Fate or some mysterious force can put the finger on you or me for no reason at all."

He had no idea at the time how prophetic that line would be. Or that he would be replaying that very same scene 19 years later.

*****

Tom Neal's film career arc began its abrupt slide in 1951. That's when he got into a fist fight with actor Franchot Tone over the affections of sexy, upcoming star Barbara Payton on the front lawn of Payton's Hollywood home. Tone wound up in the hospital with a concussion and because Neal had once been a Golden Gloves champ, the public's sympathies leaned toward Tone. Soon after the fight, Payton and Tone married but he sued her for divorce a mere seven months later, accusing his wife of conducting an adulterous affair with…Tom Neal. (Barbara admitted she had been living with Tom but only because she said she was afraid of her husband.)

After this scandal Neal and Payton found they couldn't buy a job in Hollywood, which at that time was much more sensitive to the public's opinions about the stars than today. (Ironically, in one of the last pictures either of them made, the 1953 Robert I. Lippert epic The Great Jesse James Raid, Neal and Payton starred together.)

Tom Neal ended up selling everything he owned and moving to Palm Springs where he started working as a gardener, a trade he said he'd learned by watching Japanese gardeners who trimmed the hedges of his former two-acre estate back in Bel Air. Payton, cashing in on her blonde good looks and whatever Hollywood contacts she still had, eventually became a hooker and was arrested multiple times for prostitution, drunkenness and for kiting bad checks. In 1963 she made a brief celebrity comeback when she recounted her slide from stardom into a life of decadence in her lurid autobiography I Am Not Ashamed.

Tom Neal ended up selling everything he owned and moving to Palm Springs where he started working as a gardener, a trade he said he'd learned by watching Japanese gardeners who trimmed the hedges of his former two-acre estate back in Bel Air. Payton, cashing in on her blonde good looks and whatever Hollywood contacts she still had, eventually became a hooker and was arrested multiple times for prostitution, drunkenness and for kiting bad checks. In 1963 she made a brief celebrity comeback when she recounted her slide from stardom into a life of decadence in her lurid autobiography I Am Not Ashamed.

Neal eventually worked up a small but respectable landscaping business in the Springs and in 1961 married his third wife Gail, then 25 years old, who worked as a receptionist at the Palm Springs Tennis Club. A life of peaceful domesticity was not in the cards, however.

*****

On the night of April 1, 1965, Tom Neal entered the Tyrol, a restaurant in Idyllwild [a mountain resort near Palm Springs]. One of the owners, Robert L. Balzer, a friend of Neal's and Gail's, was surprised to see Neal alone, as he was a gregarious person and usually frequented the restaurant with groups of people. When Balzer and his partner, James Willett, sat down to talk with Neal, Balzer noticed Neal seemed troubled and asked what was the matter.

Neal began talking about his previous wife, Patricia, who had died of cancer in 1958, two and a half years before he married Gail. He said since that time Gail had become his entire life and he could not live without her.

Neal began talking about his previous wife, Patricia, who had died of cancer in 1958, two and a half years before he married Gail. He said since that time Gail had become his entire life and he could not live without her.

And then he told the pair he'd just killed her.

Thinking Neal was kidding, Balzer and Willett chided him but were stunned when he said, "It's not an April Fool's joke; it's true," adding that he had shot Gail to death earlier in the day as she lay taking a nap.

The next morning at 6:30 a.m. Palm Springs police received a call from James Cantillion, Neal's Beverly Hills attorney, asking to have officers meet him at the Neal's home at 2481 Cardillo Road. Cantillion said that a woman there "had expired or was seriously injured." Heading to the location, Patrolman Joe Jones was flagged down by another attorney, James Kellam, who led him into the house. The body of Gail Neal was lying on the couch, partially covered by a bedspread. She had been shot behind the right ear with a .45 automatic. The spent cartridge was found four feet away. It was then that Cantillion surrendered Neal to the police.

An autopsy later revealed that the death had taken place between 2:30 p.m. on April 1 and 2:30 a.m. April 2. Nobody in the neighborhood had heard the shot, but one neighbor said she'd heard "yelling and screaming" two nights before and loud arguing on other occasions.

On April 16 the Riverside Grand Jury indicted Neal for murder. Since his arrest, Neal had been represented by Riverside County Public Defender James Kellam but on August 20 Neal made an appearance before Judge Hilton McCabe, who was to preside over the trial. Neal asked for a continuance due to a request for change of counsel, complaining that Kellam had never visited him in jail since the April arrest. Later, when asked to comment, Kellam confirmed Neal's claims, saying, "It was a negative action. I felt that Neal needed a better defense than a public defender could provide and that through non-action, I could force his friends to come to his aid." Kellam estimated Neal would need up to $15,000 to put on an adequate defense. "The situation is this," he told reporters: "The court allots something like $500 for the defense of such a case as this. It's a mere pittance."

Kellam's "non-action," in fact, did force Neal's friends to come to his aid. Cathedral City auto dealer Glenn Austin, for example, kicked things off by taking out an ad in a local paper soliciting contributions for the Neal defense fund. Local friends of Neal began to send in checks and soon Hollywood, the town that had turned its back on him years before, responded, with celebrities like Mickey Rooney and Blake Edwards, columnist Dorothy Manners and Harrison Carroll, and, ironically, Franchot Tone, the man responsible for Neal's fall from grace, all contributing to the fund.

Kellam's "non-action," in fact, did force Neal's friends to come to his aid. Cathedral City auto dealer Glenn Austin, for example, kicked things off by taking out an ad in a local paper soliciting contributions for the Neal defense fund. Local friends of Neal began to send in checks and soon Hollywood, the town that had turned its back on him years before, responded, with celebrities like Mickey Rooney and Blake Edwards, columnist Dorothy Manners and Harrison Carroll, and, ironically, Franchot Tone, the man responsible for Neal's fall from grace, all contributing to the fund.

Neal responded to Austin's efforts on his behalf in a two-page note handwritten in pencil: "You 'my friend' have swept away dark clouds that were threatening to engulf me." In the note he also laid the blame for Gail's murder on a "friend," although he did not give a name. "People who I thought were my friends – they prejudiced me," he wrote, "and with friends like that (who drank my booze, ate at my table and gunned my wife), who needs enemies?"

With money from the defense fund Neal was able to procure the services of Leon Rosenberg, a Palm Springs attorney who had gotten his law degree while serving as a clergyman. Rosenberg agreed to take the case after conferring with Kellam and speaking with Neal.

*****

On October 19, 1965, the trial opened with Deputy D.A. Roland Wilson, a man short in stature but long on prosecutorial experience, laying out his case against Neal and asking for first-degree murder conviction. After Rosenberg waived his opening statement, reserving the right to make it at a later time, Wilson began with the damning testimony of Balzer and Willett, to whom Neal had "confessed."

He then put on the stand Frank Seyferlich, a local real estate broker and friend of the Neals who had been at their house the night before the shooting. Seyferlich testified that he arrived at the house between 5:30 and 6:00 p.m. He'd gone to the house to deliver letters of recommendation for Gail, who intended to divorce Neal and move to Los Angeles and needed references to get employment. Gail Neal answered the door and invited Seyferlich in for a drink, which he declined, saying he was in a hurry. Gail Neal then said, "Well, at least come in and see who's here."

When Seyferlich entered the house, he was surprised to see Tom standing by the fireplace. The couple was separated and Tom had been in Chicago since January and, according to Seyferlich, Neal "looked a little nervous and tired, perhaps from the trip." Knowing about the couple's marital problems but not knowing if Tom Neal knew about his wife's intentions to divorce him, Seyferlich felt uncomfortable and asked to be excused, but Gail again insisted he stay for a drink. "No," the real estate man told her, "you two have a lot to talk over."

For the next two days the prosecution questioned police and forensic investigators, laying out the physical evidence. The plot began to thicken during Rosenberg's cross-examination of laboratory technician H. Carmon Bishop. During previous testimony Bishop had testified he found a man's wallet in the top drawer of the bureau in the Neals' master bedroom. "Did you open the wallet?" Rosenberg asked.

"Yes."

"Did you find anything in that wallet which would indicate to whom it belonged?" Rosenberg asked.

Before Bishop could answer, the prosecutor was on his feet, objecting on the grounds that the answer was "hearsay and immaterial."

However, Judge McCabe sustained the objection and Rosenberg went on to elicit testimony from Bishop that he had also found a man's suitcoat hanging in the closet of the master bedroom. Although Rosenberg did not establish the identity of the coat's owner, he left no doubt in the minds of the nine-woman, three-man jury and the minds of the public who read the papers the next day that the wallet and the coat did not belong to Tom, raising the specter of the killer "friend" Neal had alluded to in his note to Glenn Austin.

On October 28 after calling only eight witnesses, the prosecution in a surprise move rested its case, catching Rosenberg completely off-guard. The flustered attorney told McCabe: "I am, I confess, caught a bit unprepared," and asked for a continuance, which was granted until the following day.

On October 28 after calling only eight witnesses, the prosecution in a surprise move rested its case, catching Rosenberg completely off-guard. The flustered attorney told McCabe: "I am, I confess, caught a bit unprepared," and asked for a continuance, which was granted until the following day.

Pulling his act together, Rosenberg then put Chief of Detectives Richard Harries on the stand. Harries established the identity of the "mystery" man whose belongings had been found in the Neal home. It was Palm Springs insurance man Steve Peck who lived in a spare bedroom in the house and paid half the rent. But if Peck lived in the spare bedroom, what were his wallet and coat doing in Gail Neal's closet? It was quickly established, however, that Peck had been in Phoenix at the time of the shooting and had witnesses to prove it, eliminating him as the killer. But Rosenberg also got Harries to admit that in spite of an intensive search, the murder weapon had never been found. However, whatever mileage Rosenberg got out of that fact was quickly taken away on cross-examination when Harries told the prosecution that he had found a live .45 automatic bullet in the pocket of Neal's jacket at the time of his arrest as well as a box of similar ammunition in the Neal's hall closet. It wasn't looking too good for Tom Neal.

The next day Rosenberg hinted what his strategy was going to be; he called Steve Peck to the stand. Peck told a riveted jury that the previous November he had been present during a domestic quarrel between the Neals in the hallway of their house. According to Peck, Gail emerged from the bedroom with a .45 automatic, screaming at Neal, "I'll kill you, you bastard!" Peck testified that he wrested the gun out of her hand after which Neal "calmed her down." But under cross-examination, Peck's credibility was called into question when he admitted that in his original statement to police, he'd said Tom Neal had been the one brandishing the gun after he had slapped his wife several times. Peck insisted, however, that his current recollection of the event was the truth and his statement to the police had been incorrect.

Then came what the public had been waiting for. Tom Neal took the stand. Achieving in the courtroom what had escaped him in his film career – top billing – Neal recounted his version of the fatal evening. Under Rosenberg's questioning, Neal told jurors that just before the shooting, Gail had been lying on the couch and he had been on one knee, caressing her.

"Was she resisting anything you were doing?" asked Rosenberg.

"No, she wasn't resisting," Neal replied. "I think at that time she said, 'I don't know whether we should do this, Tom.' And I said, 'Don't be silly, I've been away for ten weeks and you have been fooling around with all these guys since I left, and even before I left.'

"No, she wasn't resisting," Neal replied. "I think at that time she said, 'I don't know whether we should do this, Tom.' And I said, 'Don't be silly, I've been away for ten weeks and you have been fooling around with all these guys since I left, and even before I left.'

"'Oh, I just couldn't help myself,'" Gail allegedly told Neal, after which the two began to argue. After Neal accused her of having sexual relations with his friends he "felt her body tense and the next thing I knew, I heard her yell at me, 'I'll kill you, you bastard!'

"I looked up from where I was – and what I faced was the .45 automatic in her hand."

"What did you do?" Rosenberg asked.

"I was down on one knee and…I mean, it was all simultaneous and she…I said, 'Gail are you out of your mind?' and with that I shoved the gun with both hands from the position I was in and the gun went off."

"Did you do anything after that?"

"I prayed," Neal said dramatically. "I took her hand, I called her name, 'Gail! God no! Gail!' Then I said aloud, 'There is no life, truth, intelligence or substance in mind, all in infinity and its manifestation, for God is all in all. Spirit is immortal truth, matter is mortal error. Spirit is the real and eternal, matter is the unreal and temporal.'"

"Is that what you said at the time?" Rosenberg asked.

"Yes, sir."

"Did you say anything else?"

"Yes…talithucumi, which is interpreted as 'Fair maiden arise, for thou art whole.'"

Then he testified that he drove to the Tyrol restaurant where he said he had told Balzar and Willett only that his wife "had been shot" and that he felt responsible for it, not that he'd shot her.

With that Tom Neal finished his final performance.

On November 9 prosecutor Roland Wilson called to the stand Dr. Armand Dollinger, the pathologist who had performed the autopsy on Gail Neal. Dollinger told the jury that Neal's account of the shooting was "unlikely."

"Considering the direction of the wound," Dollinger told the court, "it would require one's wrist to be extremely flexed and the index or trigger finger would tend to pull away from the trigger."

Rosenberg tried to discredit Dollinger's testimony by asking whether the pathologist had measured Gail Neal's arm or had any knowledge of the muscle structure of her hand. The answer to both questions: "No."

Wilson followed up with three of Gail Neal's co-workers from the Palm Springs Tennis Club. They testified that Gail had planned to leave town when she heard Neal was returning from Chicago because she was afraid he would kill her when he learned she had filed for divorce on March 11. In the divorce complaint Gail had charged Neal with threatening her with a .45 automatic the previous November.

After 20 days both sides rested. The jury deliberated for ten hours and returned with the verdict: Involuntary manslaughter. This seemed to stun the prosecutor.

An elated Rosenberg told the press: "We had a longer way to go in this case than the prosecution." The lawyer added that because of time served Neal could be out by Christmas.

But any hopes Rosenberg had of that were crushed the following month. After Rosenberg pleaded with Judge McCabe for probation, citing the actor's previously clean record and terming the events of April as the "tragic culmination of a period of marital instability," prosecutor Wilson, presented his side: "The district attorney will not consider probation for the defendant…The fact the jury brought only a verdict of involuntary manslaughter is as big a break as Mr. Neal deserves." Judge McCabe agreed, sentencing Neal to up to 15 years in state prison.

Neal bit his lip during the sentencing but kept his composure. Outside the courtroom as he was being whisked off to county jail, he told the press the sentence was a "railroad job."

So ended one of the longest and most publicized trials in the history of the Indio court. The case got so much publicity, in fact, that it precipitated Earl Neel, the owner of Neel's Nursery and later Palm Springs city councilman, to take out a full-page ad in the local paper: "My name is Neel," the ad read, "not N-E-A-L. I didn't kill anyone. I'm not even married."

Throughout the trial Barbara Payton had been in the gallery and she and Neal waved to each other. That was the last time they would ever see each other again.

*****

Neal was paroled from prison on December 6, 1971, after serving seven years. He moved to Hollywood, the scene of his rise and fall, and died there of natural causes a year later at the age of 59.

The famous line from Detour resonates: Fate or some mysterious force had put the finger on Tom Neal for no good reason at all. PSL