This summer, Mart Crowley’s The Boys in the Band recently celebrated its golden anniversary on Broadway featuring an all out celebrity cast. Palm Springs resident Laurence Luckinbill originated the role of Hank in the play and then the movie, a character he described as “the guy who gives a cardigan as a birthday gift.”

Luckinbill is a gifted humorist, but he’s also a serious actor. He has undergone complete transformations playing everything from Spock’s half-brother in Star Trek V to Clarence Darrow, Theodore Roosevelt, Ernest Hemingway, and Lyndon Johnson in his one-man shows. However, the role that changed the trajectory of his career and inner monologue came in 1967 with the seminal gay play The Boys in the Band.

Luckinbill, who will put on America’s Better Angels on March 15, 2019 at the Annenberg Theatre, featuring historical videos by James Cook and music by his son, Joseph Luckinbill, spoke to Palm Springs Life about the historic gay film and what was at stake.

• Read our story about Luckinbill's wife, Lucie Arnaz, and her famous parents memoirs.

What did you think of the script?

There was a lot of violence, sado-masochism, and it was not only rip-roaringly funny but funny in a genuine way. It was written by my friend Mart Crowley, who I had gone to college with. After I read it, I met with him at a bar in Sheraton Square.

Mart told me he’d gone around New York trying to get people to read the play. Producers did not want to read it. Straight actors wouldn't look at it, and gay actors didn't want to do it because they were in the closet. As Mart told me this story, he was clutching his script close to his heart, like a baby. I said, "Mart, I'll do it," and he started to have a little cry, then he wiped it away and said "Thank you."

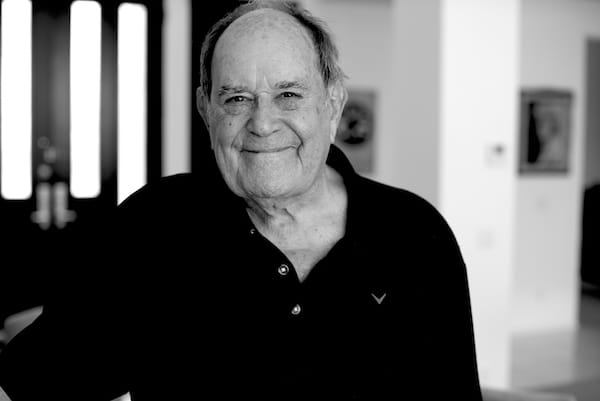

PHOTOGRAPH BY STEVEN SALISBURY

Laurence Luckinbill, 83, lives in Palm Springs with his wife of 38 years, Lucy Arnaz.

I told my [former] wife, Robin Strasser, who was a New Yorker, a smart gal, and very liberal, so that was fine. Then I told my agent, who was not only my agent and Mart’s agent, but a lesbian married to a gay man. She was distraught and divided. She said, "You're right at the edge of being able to get where you want to get. Do you really want to do this?” I did. “OK,” she said, “there goes your career.”

Can you tell us a little bit about the rehearsal process?

The production was at Edward Albee’s playwrights unit. It was going to be a five-day run, rehearsal about a week. Nobody was being paid, and Eddie had a rule: none of the work produced was to be reviewed by the newspapers. It was purely to give Mart and the producers a chance to look at the play and see if it worked. [Director] Robert Moore was a gay man from Catholic University where Mart and I went to school, and one of the producers who was also gay, went to Catholic University. It was a gay-Catholic show.

I wanted to rehearse more, but Equity protects fools and actors. So we had to work it out ourselves within the five shows.

VIDEO: Laurence Luckinbill answers 2 questions not included in the interview you're reading.

How was opening night?

It was chaotic. We were all trying to find our rhythms.

But the next day, I had to get to the bank early and deposit my $135 check from The Secret Storm [a CBS soap opera] because my rent was coming due. I was walking across the street by the theatre and I saw this huge crowd of people out front and thought, “Oh no! There's a fire and the theatre burned down.” Then I realized — there's no sirens, no trucks. Then I saw people were not just standing there, they were in a line that went all the way up to 6th Avenue and into the West Village. It was unbelievable. There must have been four or five hundred people waiting.

I knew the tiny theatre had been booked solid for the five-day run with relatives and producers and agents, and here are these people standing in minus six degree weather. You could see the breath from their mouths, stamping feet to keep warm, yet they were happy and laughing. Then I saw that everyone in the line was gay. I stopped in my tracks. I realized that overnight, the telephone game had started and word of mouth got out, and I thought, “The closet door has been opened by this tiny little play. If there's 500 people there now, what's going to happen with this play?”

That set a course for me. It's like somebody came and said, “OK, here's your compass heading, this is what you need to do. You're going to judge everything from this from now on. This kind of social value, this value of opening doors and freeing people.” I started to cry, I wiped my eyes. At that time I couldn't have articulated these things, but now I can.

Did you see the new production of The Boys in the Band?

I told Lucie [Arnaz, his wife] I wasn't going. But then Lucie’s lawyer, Mark Sendroff, said "why don't you go to represent the others?" And I said, that's the real reason to go, to represent all the guys that have died. Because everyone is dead except Peter White, me, and Mart — not just the actors but the entire stage management staff, the entire production staff, the director and press people, about 20 people from the production all went in the AIDS epidemic.

In a scene from The Boys in the Band, (from left) Laurence Luckinbill, Peter White, and Frederick Combs.

So I went for that reason, and I said those things and got to compliment Mart. Because it was his courage ... he insisted that the original cast do the film. He had offers for quite a lot of money to dump us and get Hollywood actors but who were they going to get? Rock Hudson, Roddy McDowell? Gay actors who were not out? Mart's insistence got me a two-picture deal with Otto Preminger, a bunch of television films and a series. All the hooha didn't do the other actors as much as it did for me. Well, Leonard [Frey]. But he was already working; he was in Fiddler on the Roof, and he was so extraordinary looking it didn't matter whether he was gay or green. A sensational actor.

Do you think The Boys in the Band still packs the same punch it did in the 1960s?

Lucie and I were supporting a candidate for city counsel that we liked, and he asked me if I'd come to his house and give a little speech for him and about 20 friends. I said sure, give me a list of things to say about you and the issues. And he said, "I don't want you to do that. I want you to read from your memoir, Famous Enough.” I've been writing it for two years, and I'm about another year and change away from finishing. So I read from my chapter about The Boys in the Band. Everyone was holding pins but they would not drop them; it was that quiet. At the end they stood up and gave such applause for the play — and themselves, really. For their survivorship. They understood it from the inside out.

There’s a wonderful composer who lives here in Palm Springs who told me, "When I was 17, I saw the movie. I knew I was gay but I did not know how to come out or if I wanted to. It was dangerous. I was in law school, and when I saw your character of Hank, I wanted to be like that guy because Hank is courageous, he is telling the truth, and he's not sorry about it."

I realized that little part that I just stepped into like it was a cardigan was the spiritual center of the play.

Do you have a favorite line from the play?

Harold’s last line, “Call you tomorrow.” This group of guys could tear each other apart, but at the heart of it, they loved and needed each other. That line says it all.

To view the film on YouTube, click HERE.