Have you ever navigated through a space that looked like an abandoned forest of tourist merchandise or an otherworldly light show only to find out that it was art? Maybe you’ve seen a site-specific sculpture in a public space, museum, or even corporate lobby? If so, you are already acquainted with installation art.

But have you considered what it would be like to live with it?

Art collectors typically live with paintings and works on paper. Most at least consider owning sculpture. Others go further by purchasing and maintaining space-invading artwork. They would have it no other way.

Installation art can be broadly defined as a work of art that incorporates and transforms the space around it. This genre exists indoors or outdoors and has no boundaries in terms of material. Implicitly, installation art addresses more than one of the five senses, because it exists out of the normal context in which we receive art. Anything you’ve seen that requires more interaction — for example, walking on, under, or through a sculptural form — can probably be considered installation art.

Palm Springs Life visited the homes of three couples who live with installation art — Diane and David Waldman of Rancho Mirage, Molly Bondhus and Wil Stiles of Palm Springs, and Donna Tuttle Elmore and David Elmore of Palm Desert — and found their common experience calls for an implied contract: By demanding more of the viewer, it returns more to those who give it their care and attention.

DIANE AND DAVID WALDMAN

For David and Diane Waldman, living with installation art is a true calling. Their house is full of structural forms made from industrial metal, fencing wire, used olive oil cans, and other artistic whimsy: most prominently, a full-size automobile sheathed in leather — “Boy” (1999) — by Michelle Lopez that occupies the center space in their living room.

For David and Diane Waldman, living with installation art is a true calling. Their house is full of structural forms made from industrial metal, fencing wire, used olive oil cans, and other artistic whimsy: most prominently, a full-size automobile sheathed in leather — “Boy” (1999) — by Michelle Lopez that occupies the center space in their living room.

“We like to engage in a dialog with the works,” says Diane, who maintains long-term friendships with “art mentors” (mostly artists) who share insight about their practices and introduce the couple to other interesting artists.

Sometimes, these often-unwieldy creations can be impractical. “We have more work in storage than we should admit to,” Diane says, adding that she is unafraid to take a risk on a work she believes in.

“The piece by Lopez is a perfect example,” Diane says. The Waldmans met the artist when she and her then-boyfriend, artist Peter Schuyff, called from New York asking them to help Lopez remove her sculpture after its installation ended at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions.

“As a favor to Peter, we agreed to go and see the piece, but were quite skeptical when he described a ‘leather-covered car,’” Diane says. “I convinced David we should go and look; so we drove into L.A. and, to our surprise, really liked the piece. Without thought to placement, we bought it. I have a theory that work finds its own space, and that has usually worked out. David, on the other hand, often has ideas of where he would like a work to be and is often amazed to find that the work has other ideas and looks better elsewhere.

After an epic ordeal removing the car from LACE and transporting it to their ranch house near Idyllwild, the Waldmans took a call from Jeffrey Deitch, Lopez’s New York gallerist turned director of Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Deitch wanted the piece for Greater New York, the first collaborative exhibition between New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center. “We were thrilled for Michelle and agreed to lend the work,” Diane says, adding that the show gained attention in Art in America, Newsweek, Time Out New York, and The New York Times.

“Incidentally, ‘Boy’ is a real car that Michelle found in Joshua Tree National Park and hauled to Los Angeles for her show at LACE. She softened vegetable-tanned buffalo leather skins and draped them over the shell inside and out. The seats are removed so you can lie down inside the car and look up at the cartoonish landscape that Michelle scribed and painted on the interior. The first time my granddaughter, Charlie [18 months old at the time], saw the car, she crawled in and we could hear her giggling. From that moment on, it became our special place. Now, granddaughter No. 2, Izzie, joins us. … It becomes a real adventure when our dogs — Great Dane Agnes, Bernese Mountain Dog Louis, and German Shepherd Toby — climb in with us.

“People are always surprised to find a car in our living room,” Diane continues. “This sculpture found its place and is very comfortable where it is. David and I never think about where we will put a piece of art. It has gotten us into a lot of trouble; we have work with nowhere to go. It is part of the addiction and love of art; and it is sometimes a mystery, but always an adventure.”

MOLLY BONDHUS AND WIL STILES

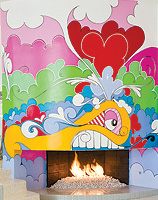

Molly Bondhus and Wil Stiles live in a 1963 circular midcentury house designed by R. Denzil Lee in Palm Springs’ Mesa neighborhood. As proprietors of the hip boutique Wil Stiles on North Palm Canyon Drive, they are ardent design fans and admirers of large-format outdoor muralists such as Banksy and John Grider. For their living space, they commissioned renowned street artist Eric Inkala of Minneapolis to create a site-specific, 9×12-foot acrylic mural on their main interior wall.

Molly Bondhus and Wil Stiles live in a 1963 circular midcentury house designed by R. Denzil Lee in Palm Springs’ Mesa neighborhood. As proprietors of the hip boutique Wil Stiles on North Palm Canyon Drive, they are ardent design fans and admirers of large-format outdoor muralists such as Banksy and John Grider. For their living space, they commissioned renowned street artist Eric Inkala of Minneapolis to create a site-specific, 9×12-foot acrylic mural on their main interior wall.

Inviting Inkala to stay with them for 10 days while he completed the piece, Bondhus and Stiles committed to allowing the artist to paint directly on the wall. “Several friends could not understand,” Molly says. “They figured that if it was on a canvas, we could move it or take it with us if we ever sold the house. While we had considered this option, it never seemed like a good fit for the nature of the art.”

This bright, optimistic piece demonstrates the couple’s strong commitment to living with art that they love. “Eric had very little difficulty working on the interior, curved, fireplace wall, given his background as a street artist who was accustomed to working on irregular outdoor surfaces,” Molly says. The biggest challenge for the artist “was doing a piece on such a large scale entirely in acrylic (one of the few limitations we gave him). He would have typically used aerosol paint on such a large piece. It was much more time-consuming as a result.”

Bondus and Stiles’ appreciation for the work remains steadfast after three years. “It still makes us smile,” Molly says. “Viewed from outside, with the rock of the mountain rising behind the home, it creates a spectacular juxtaposition of natural and unnatural. In fact, it is still the only wall of our home — inside or out — that is painted with any color.”

DONNA TUTTLE ELMORE AND DAVID ELMORE

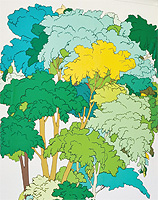

Collectors with an affinity for wall-size works of art that break traditional boundaries of two-dimensional painting need not all hire muralists to set up shop in their houses. Many prefer the colorful graphic possibilities of vinyl wallpaper, long popular for commercial advertising. “This [wall vinyl by artist collective assume vivid astro focus] has a somewhat baroque feeling, but would only work in a space with angular, modern lines,” suggests Donna Tuttle Elmore, who collects mostly California minimalism. She revamped the molding on her 11-foot-high walls to accommodate “Cleland Tree” (2003).

Collectors with an affinity for wall-size works of art that break traditional boundaries of two-dimensional painting need not all hire muralists to set up shop in their houses. Many prefer the colorful graphic possibilities of vinyl wallpaper, long popular for commercial advertising. “This [wall vinyl by artist collective assume vivid astro focus] has a somewhat baroque feeling, but would only work in a space with angular, modern lines,” suggests Donna Tuttle Elmore, who collects mostly California minimalism. She revamped the molding on her 11-foot-high walls to accommodate “Cleland Tree” (2003).

She chose to install the tree-size graphic in three dimensions, spanning perpendicular walls of the foyer in her and David Elmore’s Marrakesh Country Club house. According to the artists’ original intentions, the work may be infinitely recreated in any format or media, as long as there is only one copy in use at any given time. Still, the Elmores have no plans to do so anytime soon. “It feels like it belongs here,” Donna says. “The surface picks up subtle tones in the other works around it — and even the exterior light.

“It’s fun and unlike anything else we have, and our guests love it,” she continues.” With an intentionally murky biography and complicated edition system, assume vivid astro focus requires some vision by prospective buyers. “We knew where we wanted to put it, so it was mostly a matter of choosing the right image and size,” Donna says. “The actual artwork is a digital file stored on a disc, so what you see here is really just its current incarnation.”