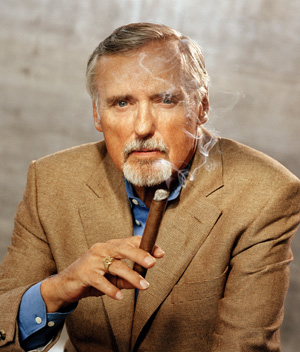

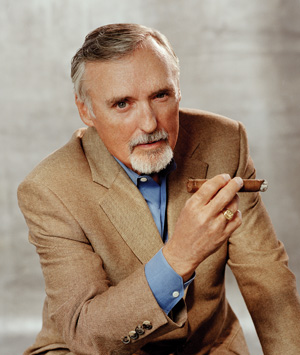

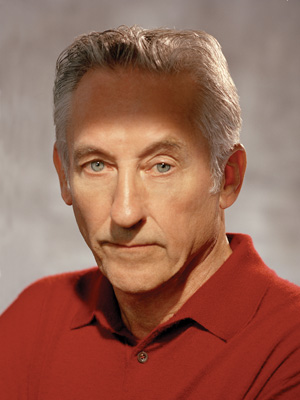

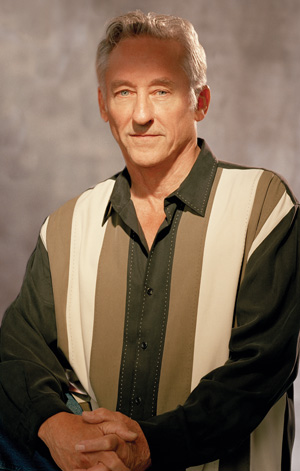

Photography by Michael Childers

Thirty-eight years since he filmed Easy Rider (1969), Dennis Hopper still revels in the roar of a well-appointed hog and the open road to put the pedal to its mettle. On a recent joy ride in the United Arab Emirates, the actor/film director/artist/art collector tagged along with free-spirited Guggenheim Foundation Director Thomas Krens, with whom Hopper co-founded a loosely organized group of celebrity bikers (including Frank Gehry, Laurence Fishburne, and Jeremy Irons). This particular occasion coincided with the launch of the new Gehry-designed Guggenheim in Abu Dhabi.

Incidentally, Krens conceived The Art of the Motorcycle, the most popular exhibition in the 62-year history of New York’s Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Guggenheim, and has overseen four Guggenheim museums, receiving an equal measure of darts and laurels for his globalization of the institution. (Village Voice art critic Jerry Saltz has called for his ouster, saying, “The trustees and board members who helped [Krens] twist this … into a kind of GuggEnron should go as well.”)

It only serves to reason that Gehry, one of the world’s most daring architects (he even appeared in Apple Computer’s “Think Different” campaign) would align himself with such rogues. Gehry ignites fury and adulation with nearly every design he unveils. His arresting — and often iconic — structures include the silver sails of downtown Los Angeles’ Walt Disney Concert Hall and the titanium-paneled Guggenheim building along the banks of the river in Bilbao, Spain.

Gehry, 78, and Hopper, 70, share a nonconformist spirit that came to define Los Angeles in the mid-1950s — the same time Ed Ruscha (pronounced roo-SHAY) arrived from Oklahoma City to attend Chouinard Art Institute. In little more than a decade, the young artist broke new ground by casting words and phrases onto his canvases and works on paper. He also experimented with a variety of media, most notably gunpowder. His selection as the U.S. representative at the 1970 Venice Biennale put him — and Los Angeles — firmly on the art world map. That installation consisted of a salon lined wall to wall with silk-screened chocolate on paper, engaging all senses. Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art re-created the chocolate room for the exhibition Cotton Puffs, Q-Tips®, Smoke and Mirrors: The Drawings of Ed Ruscha.

>

Ruscha, 69, redefined the way we observe the Los Angeles landscape. “No American artist has a more singular vision of the American landscape, especially the impassive iconography of the road, than Ruscha,” says Adam D. Weinberg, the Alice Pratt Brown director at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, which also exhibited the show.

Gehry, Hopper, and Ruscha will be honored on March 24 at Palm Springs Art Museum’s Artists and Legends Gala. The timing of this second-annual event — presented by the fundraising-focused Museum Associates Council — could be no better. These Artistic Achievement Award recipients need a break from their never-say-die schedules.

FRANK GEHRY

Forget exacting grids and mind-numbing mathematics. When Gehry designs a building, he turns to the tools of an artist. He loves drawing sketches and building models. Like-wise, we look at his structures as sculptures — loaded with gesture, assemblage, collage, and tons of integrity. Gehry won the 1989 Pritzker Prize — the Nobel of architecture — nearly a decade before he unveiled his titanium masterpiece: Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao.

Lauded by CNN as a “contemporary marvel” along with the Hubble Space Telescope, International Space Station, and DNA fingerprinting, Guggenheim Bilbao draws as many tourists and architecture buffs from around the world (more than 2 million since its late-1997 opening) for the sheer spectacle of the structure as it does for the fine art inside. From the calm Nervión River bank, it looks like a futuristic luxury cruise liner. On the other end, Puente de La Salve (one of the main access routes into the city) appears to pierce the structure. From any vantage point, visitors marvel at its shimmering iridescence, dramatic curves, and abrupt angles. Immensely functional, the building has changed the way we look at architecture and made Bilbao, the Basque capital of Spain, a cultural destination.

Today, the architect born Frank Goldberg in Toronto who moved to Los Angeles in 1947 and earned his architecture degree from University of Southern California in 1954, sits at the helm of Frank O. Gehry and Associates, the firm he opened in 1967. His name surfaced in the early 1970s with the introduction of his furniture lines: Easy Edges (squiggly, laminated cardboard chairs, stools, and tables for the masses) and Rough Edges, which were available in limited editions at galleries. But the industrial renovation of his own pink Santa Monica bungalow in 1978 gained him the attention that won him marquee commissions.

The house, which he tweaked in 1991 to gain privacy, was the harbinger of his deconstructivist, corrugated-metal signature. But he’s hardly locked to a single aesthetic. That same year, on Main Street in nearby Venice, he unveiled the Chiat/Day building — a white structure and a copper-plated structure flanking a three-story (45 feet tall) pair of binoculars conceived by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen.

When Walt Disney Concert Hall (home to the Los Angeles Philharmonic and maestro Esa-Pekka Salonen) opened in 2003, critics wrote that it either mimicked Bilbao or eclipsed it as his greatest work.

Like Bilbao and the Sydney Opera House, Gehry’s most recent building — the New York headquarters of Barry Diller’s InterActiveCorp — offers a wealth of vantage points. However, New York Sun critic James Gardner, among other critics, suggests the design’s function falls short and wondered in print if Gehry’s deconstructivist sensibility was appropriate.

“Doubtless its very clumsiness was in part intentional,” Gardner wrote. “There has always been a whiff of ruckus rodeo to Mr. Gehry’s architecture, a sort of awe-shucks, all-American populism that proudly rejects the sheer symmetries and austere high-mindedness of European Modernism. … And yet, here as elsewhere, we must remind ourselves that simply because there is a coincidence of intention and result does not necessarily validate a cultural artifact.

“And call me old-fashioned,” Gardner continued, “but I have always felt that buildings should have doors. You know: entranceways or, at the very least, exits. In the present building, these are almost nowhere to be found, and when at last they are discovered loitering along the side streets, they seem so timid and self-effacing that they might as well not be there at all.”

Meanwhile, Gehry’s recurrent exploration of the deconstructive aesthetic continues to achieve groundbreaking results — always true to his prevailing philosophy, stated in the 1980 edition of Contemporary Architects: “I approach each building as a sculptural object, a spatial container, a space with light and air, a response to context and appropriateness of feeling and spirit. To this container, this sculpture, the user brings his baggage, his program, and interacts with it to accommodate his needs. If he can’t do that, I’ve failed.”

Sydney Pollack’s acclaimed documentary Sketches of Frank Gehry (2006) turned the big-screen lens to the evolution of the architect’s drawings and models into three-dimensional forms and, ultimately, buildings of titanium and glass, concrete, steel, wood, and stone. The film explores Guggenheim Bilbao, Marques de Riscal winery and hotel in Spain’s Rioja wine country, and the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, Germany.

While the critics do what they do best, so does the laid-back Gehry, who continues to parlay Los Angeles sensibilities into architectural icons. Next up: New World Symphony’s $200 million new home in Miami Beach, set to open in 2010.

DENNIS HOPPER

Dennis Hopper, who moved to Los Angeles in 1954 to start filming Rebel Without a Cause, is also an accomplished painter and photographer. In fact, Hopper the photographer was selected among 85 artists to show in Los Angeles 1955-1985: The Birth of an Artistic Capital, the largest and most important survey of Los Angeles art installed in a foreign museum. His dashboard photograph Double Standard (1962) was the show’s marquee promotional image.

“That was incredible,” he says. “I didn’t get to go to the opening because I was working at the time. I went over later. To see [Double Standard] on the side of Pompidou, on the subways, and in public was like a dream.

“I felt that the whole idea that there was no significant art in L.A. before 1955 was quite remarkable,” he continues. “The idea that there was a birth of an art capital — it seems only the French can pinpoint that one.

“I’d have liked to see that show go to New York. I think it had impact. The catalog is an important document about that period of time. Hopefully, the historians will re-look at this period, and that’s basically what [curator Catherine Grenier] was asking for: the late 1950s/early ’60s re-examined.”

Best known for his roles in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), Giant (1956), Easy Rider (1969), Apocalypse Now (1979), and River’s Edge (1986), Hopper turned to photography in 1961, as fewer acting roles came his way, and he concentrated on billboards. “L.A. didn’t seem to have any history at all,” he says. “It seemed it would be destroyed and be another parking lot. The only things that were interesting to me were billboards.”

Hopper was 20 when Vincent Price gave him his first piece of art and told him that he’d one day be a collector. He was in the right place at the right time: He bought Andy Warhol’s first soup-can painting for $75 and Roy Lichtenstein’s Sinking Sun for $1,100 (it sold at auction last year for nearly $16 million).

Pop art had a profound impact on Hopper’s photography. “I remember Irving Blum showing me a picture of a soup can and comic book, and I said, ‘That’s it,’” Hopper says. “[Blum] said, ‘What’s what?’ And I said, ‘The return to reality.’”

Hopper — who directed the controversial gang film Colors (1988) — was a crowd favorite last December at Art Basel Miami Beach. Preceding a screening of Easy Rider at the Colony Theatre for the fair’s Art Loves Film presentation, he spoke with Vanity Fair writer Bob Colacello as part of the Art Salon program.

“I wanted to make a sort of time capsule,” Hopper says, noting that he aimed to make a film that reflected the times. “I wanted the feeling of the West. There was practically a revolution going on to stop the [Vietnam] war.”

A certain stigma prevails among actors who make art. However, the crowd appeared genuinely interested in Hopper’s photography — a medium surprisingly prevalent at Basel Miami, now North America’s largest and, arguably, most important art fair.

On the resurgence of photography, Hopper says, “Collectors have to realize photographs were made from a chemical process, and it’s all digital now. Anything made during this time is important. The idea of taking images through a camera, freezing an image, was a unique idea.”

ACE Gallery in Los Angeles recently mounted a museum-scale Hopper retrospective that included photography, as well as abstract/graffiti canvases from the early 1990s. With the help of his biking buddy Thomas Krens, the show has moved to the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, Russia.

ED RUSCHA

The first image visitors to Paris’ Centre Pompidou saw in its historic exhibition Los Angeles 1955-1985: The Birth of an Artistic Capital was Ruscha’s iconic 20th Century Fox painting Large Trademark with Eight Spotlights (1962), a 66.5 x 133-inch canvas that reinforces the artist’s place as king of Los Angeles Pop art. (The punctuation mark at the end of this 2006 show could have been one of Ruscha’s The End paintings, which resemble the scratchy frames at the end of so many Hollywood film reels.)

That’s Ruscha: Hollywood, landscape, and words. Ruscha loves words, especially how they communicate within a particular environment or context. This is where the artist distinguishes himself: The action around Ruscha often manifests as abstract gestures, if not realist landscapes, with words and phrases stopping viewers in their tracks.

The famous Hollywood sign, Ventura Boulevard, Laurel Canyon, and the streets and scenes of Los Angeles made a star of Ruscha, once a graphic artist who created layouts for Artforum magazine, which was based in Los Angeles when he arrived in the city in 1956.

By 1963, people discussed Ruscha in the same breath as Warhol, Lichtenstein, Wesselmann, Rosenquist, and other icons of the Pop movement. Combining city- and landscapes with vernacular language, Ruscha began freshly expressing the urban experience and showing his work at the forward-thinking Ferus Gallery, the Los Angeles venue that was first in the United States to exhibit Warhol’s soup-can paintings.

In 1968, Ruscha exhibited at Galerie Rudolf Zwirner in Cologne, Germany, and later entrusted his work to the legendary New York dealer Leo Castelli. Eventually, Gagosian Gallery in New York and Beverly Hills took over representation of Ruscha’s art, which also includes films and books.

His selection as the artist representing the United States at the 1970 Venice Biennale launched him to rock-star status. Demand for his work drives the prices high into blue-chip territory. For example, Damage (1964), a 72 x 67-inch canvas, sold at Christie’s New York for $3.6 million in May 2004 (the high estimate was $2.5 million). Last November, one of his famous mixed-media works on paper, Spoil (1971), an 11.5×29-inch “ribbon” painting, went for $442,000. Indeed, the auctions fetch more than his retail prices — a telltale sign of an artist’s immortality.

Ruscha retrospectives have traveled to San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. In 2002, an exhibition of Ruscha’s entire body of work opened at Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Spain.

Two years later, Whitney Museum of American Art organized Cotton Puffs, Q-Tips®, Smoke and Mirrors: The Drawings of Ed Ruscha, which traveled to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and then to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Also in 2004, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney mounted a selection of the artist’s photographs, paintings, books, and drawings that traveled to Museo Nazionale delle Arti del XXI Secolo in Rome and to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. In 2006, Ed Ruscha, Photographer opened at the Jeu de Paume in Paris and is traveling through Europe this year.

Meanwhile, his painting No End to the Things Made Out of Human Talk (1977) hangs neatly in the internationally acclaimed Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (through March 4).

Ruscha also had shows recently at Crown Point Gallery in San Francisco and Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle (Ed Ruscha: Signs + Streets + Streets + Signs), Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena (Ooo: Early Prints by Ed Ruscha), the new Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston (a group exhibition, Super Vision), Riverside Art Museum (Greetings From the American Dream, another group exhibition), and seemingly countless other shows, including Art in America: Three Hundred Years of Innovation, the first survey of U.S. art presented in the People’s Republic of China (Ruscha was represented by his 1977 painting Back of Hollywood, from the collection of Musée d’art contemporain, Lyon, France).

His latest works — word pieces with a Sopranos twist — made their debut at the Los Angeles Art Show in January.

Exclusive Online Video Feature: Icons of Art, Film, and Design

Palm Springs Life Photo Editor Jay Jorgensen behind the scenes with Dennis Hopper, Frank Gehry, Ed Ruscha, and photographer Michael Childers.