111 East

DESIGN

Before the famed Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, there were bored teenagers.

Before Coachella, generators in the vast desert powered punk and metal bands stoked with beer and weed in places so remote there was no chance for police to bust up the party.

Before Coachella, there was Jimmy Palmer.

In 1987, 16-year-old guitarist Palmer and his band, Overdrive, were ground zero in Coachella’s generator music scene — termed “desert rock” and sometimes “stoner rock.”

And then somewhere along the line, the valley native became a car salesman.

Jimmy Palmer in his garage/workshop in La Quinta.

His story could have ended there, with Palmer successfully selling cars at Desert Lexus in Cathedral City. But as in all heroes’ journeys, Palmer met some key people, battled a few dragons, and wound up doing a job he loved. Today, he builds guitars for Aerosmith. Palmer’s two La Quinta enterprises — 111 Guitars and The Guitar E.R. — are known for handcrafted instruments and the exacting repairs required to maintain them.

“We were the first Coachella,” says Palmer, seated in his home’s two-car garage that doubles as his shop. His fuzzed hair resembles an electric charge atop his longish face. “It ruined a lot of my equipment — all that sand.”

Palmer’s teenage friends went on to form The Eagles of Death Metal and Queens of the Stone Age — Palm Desert–based rock bands launched in the mid- to-late 1990s. The former gained notoriety in November, when its concert at Le Bataclan in Paris was disrupted by the serial terrorist attacks that killed 130 people, including the band’s merchandise manager. The valley’s tightknit community of musicians all keenly felt the loss of a comrade. As an expression of solidarity, the band returned to the City of Light in February, and finished its performance at the Olympia concert hall. Palmer is part of their club: He repairs and maintains the instruments for the Eagles’ front man, guitarist Jesse Hughes.

Palmer recently built electric guitars for Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler and Joe Perry, tricking out the instruments with signature touches: Tyler’s winged heart tattoo burned into the headstock of his pink sparkled guitar, Perry’s boneyard skull trademark branded on the back of his mahogany guitar.

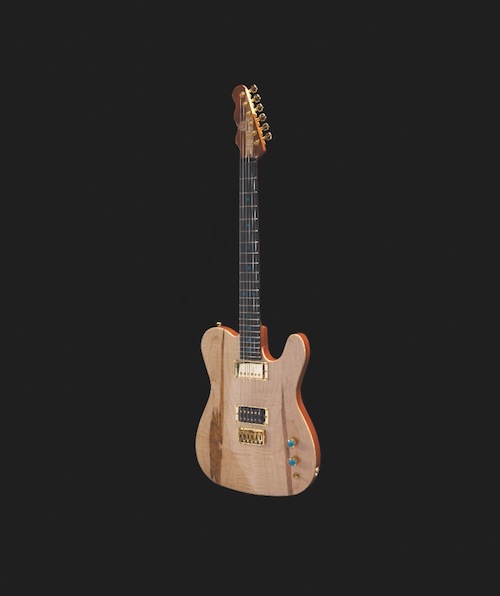

A fine specimen of a 111 Guitar, a unique creation that came from the hands of one of the desert’s native sons.

Palmer, now 44, grew up in Rancho Mirage, spent most of his 20s in Sacramento playing with the band Silent Scream, then moved back to the desert to sell cars — while learning his trade. He attended seven luthier schools, which teach the art of building stringed instruments. “Teachers at five of the schools told me I should not be in this business. They said I was too dumb,” says Palmer, who opened his shop in 2008. “When someone says that you can’t do something, and your heart says that you can — well, I had to prove a lot of people wrong.”

“His guitars are gorgeous,” says blues guitar legend Kal David, who plays Saturday nights at Palm Springs’ Purple Room Supper Club when he’s not on tour with his band Kal David and the Real Deal. “He’s got my collection really happening.”

Palmer’s work for David included securing a tremolo tailpiece on one of his three Gibson Firebirds. “I was told it couldn’t be done,” says David. “He did some engineering and ordered it gold-plated to match all the other parts. Now the guitar plays beautifully — a brilliant modification.”

Perhaps Palmer is best known for guitars that seem to have risen from the essence of the desert. Tung oil is rubbed into heavily spalted wood, strewn with contrasting lines and patterns. Palmer’s rafters are stacked with Honduran mahogany and Canadian figured maple, which he joins to form a guitar’s body that is later routed into shape.

Inlaid turquoise is fitted onto fretboards, and rounded stones are artfully placed into volume and tuning knobs. Branded into a guitar’s back: burned images of desert animals such as ravens, rabbits, roadrunners, or tortoises. The guitars, which take as long as two months to build, sell for $3,000 to $5,000.

An inlaid 111 Guitars logo (inspired by California State Route 111, commonly known by locals as one-11) is placed on headstocks, which Palmer shapes into silhouettes of the Santa Rosa Mountains. Three palm trees are burned into a headstock’s back. Palmer considers the triple digits positive numbers — primarily representing the trio of himself, his wife, Heather, and his yoga teacher, Ann Marie Palma, whom he regards as a sister. Palmer says Palma’s daily Bikram yoga classes have “changed my life forever, mentally and spiritually.”

It was Heather who told Palmer his future lay beyond being a top salesman at Desert Lexus. “She told me to quit my job,” says Palmer, who was inspired to name his repair business The Guitar E.R. because of Heather’s job as an emergency room physician assistant.

“Teachers at five of the schools told me I should not be in this business. They said I was too dumb. When someone says that you can’t do something, and your heart says that you can — well, I had to prove a lot of people wrong.”

Palmer’s greatest influence has been his mentor Uli Jon Roth, a German guitarist and pioneer in the neoclassical metal genre. In 2006, Palmer attended his first Roth Sky Academy (he’s been to eight of them), a five-day seminar that takes a holistic approach to music appreciation.

“I got to work with Uli, set up the stage, string his guitar, and make sure he got his Red Bull for the night,” says Palmer, who’s also toured with Roth as his guitar technician. “Uli really built up my confidence as I kept educating myself. He’s encouraging and transparent; the coolest guy you’ll ever meet.”

In Palmer’s garage, his shop dog Cooper —an American Eskimo breed named after Alice Cooper — snoozes in a corner, oblivious that the shop is noisy with the roar of the table saw and other machines that dominate the space along with freshly cut maple and mahogany.

Palmer bristles when discussing factory-built guitars that use plastic instead of bone for nuts atop fretboards. “Guitars are people’s babies,” says Palmer, dressed more than appropriately in a ZZ Top T-shirt. This is one guitar maker who will never cut a corner. “Tone gets sacrificed.”

Mike Pygmie, a guitarist for Mondo Generator, who has placed a custom-built order, agrees: “He treats my guitar as if it were his. He’ll fix it, and then fix things that you didn’t even know were wrong. He treats my instrument better than I do.”